America's Other Pandemic

- This article is more than five years old.

- Published on October 30, 2020 at 23:52

- Updated on January 27, 2021 at 18:35

- 21 min read

- By AFP USA

Russia's coordinated effort to nudge Americans toward voting for Donald Trump in his race against Hillary Clinton in 2016 caught social media companies flat-footed and remains a stain on the reputation of Facebook in particular.

The Internet Research Agency, operating from the city of St Petersburg on the Baltic Sea, weaponized the world's most popular online platform, seeding a covert political campaign with 80,000 posts that eventually reached an estimated 126 million people.

In the election's latter days, the trolls targeted the Midwest states of Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania, where small numbers of swing voters were prized. Trump, the unfancied underdog facing a hot favorite, narrowly won all three and entered the White House.

Four years later, the FBI and other American security officials -- aware but silent during the last campaign -- have publicly warned of foreign interference in the 2020 US election. Questions continue to be asked. Did Russia's interference make a difference? And ahead of November 3's final polling between Trump and his Democrat rival Joe Biden, could outside actors sway the outcome?

Special counsel Robert Mueller's report detailed the Kremlin's bias toward Trump and antipathy toward Clinton the last time around, but in 2020, an arguably more disturbing reality pervades: Russia is only part of the problem that Facebook, Twitter, Google and other tech companies are trying to navigate.

When it came to this presidential election cycle, Americans posted most of the false or misleading comments, memes, photographs and videos involving Trump or Biden.

"What the Russians did in 2016 was show a toolkit, where you could use deceptive actors online working in coordination with each other as a political tool," Joshua Tucker, a professor of politics and expert on data science and social media at New York University, told AFP.

"There's been a fixation on foreign interference, but the people who really have an incentive to influence the outcome of an election are people who live in that country -- Americans."

Facebook's most recent analysis of impostor activity, known as coordinated inauthentic behavior, confirmed the shift.

A different trend

In the first week of October alone, 200 Facebook accounts, 55 pages and 77 Instagram accounts that originated in the US were removed for violating the platform's rules.

Copying Russian tactics, the operators used stock profile photos and posed as right-leaning citizens across the United States. Some of the removed accounts were older, and had pretended to be left-leaning individuals around the 2018 US congressional elections.

The overall effect was to sow political discord and undermine faith in the democratic process, just as Mueller's report last year said was Russia's overarching and continuing aim.

It is now a homegrown problem.

The most egregious example recently disclosed by Facebook involved Rally Forge, a US marketing firm, that used teenagers in Arizona to post comments that were either pro-Trump or sympathetic to conservative causes, while also criticizing Biden.

The company was working for Turning Point Action, an affiliate of Turning Point USA, the pro-Trump youth group whose leader Charlie Kirk spoke at the Republican National Convention. Facebook banned Rally Forge from its platform, but did not penalize Turning Point USA or Kirk.

Rally Forge refused to comment to AFP.

Research undertaken by Tucker and his colleagues at NYU shows that political partisanship -- heightened by social media algorithms that drive users to one side of a story -- means neither liberals or conservatives are good at sorting fact from fiction when challenged.

As part of a third-party fact-checking agreement with Facebook, AFP has flagged thousands of false or misleading posts in the US since January this year. Some had been shared hundreds of thousands of times. User feedback shows that verified facts are not accepted, and often vehemently denied, when they go against partisan political belief.

Twitter is also removing impostor content. One such account featuring the image of a Black police officer, Trump and the slogan "VOTE REPUBLICAN" gained 24,000 followers earlier this month despite tweeting only eight times.

Its most popular tweet was liked 75,000 times before the account was removed for breaking the platform's rules against manipulation.

Social media researchers say the detection of such accounts are the exception rather than the norm. And when it comes to America's polarized politics, the disagreement could not be more total.

"We can no longer agree on what it means to know something," Professor Russell Muirhead, co-author of "A Lot Of People Are Saying," a book title that plays on words often used by Trump to promote unproven theories, told AFP.

"People no longer ask if something is true, but are instead asking if it is true enough to retweet."

The absence of gatekeepers, traditionally the editors of newspapers and broadcasting regulators for television and radio, has had unanticipated and often derogatory effects beyond the elixir of greater individual freedom.

"Anyone can say anything to everybody in the world for free," said Muirhead, calling social media an amplifier for disinformation.

The fake story that never died

Pizzagate, a false claim that top Democrats ran a child sex trafficking ring from a Washington, DC pizza restaurant, remains part of America's culture wars. The conspiracy theory went viral in 2016, and despite being debunked, it is an example, according to Muirhead, who teaches politics and political science at Dartmouth College, of how public discourse has been poisoned.

"This story, with no basis whatsoever, purports to show Hillary Clinton as a concentration of pure evil," he said.

"How do you make politics with such a person? You can't, so you have to make war. That story told Trump supporters that in a political context you are engaged in a war with someone who should be locked up."

The pattern has been repeated in 2020. Pizzagate metastasized, gaining a new younger audience on TikTok, before being succeeded by the QAnon conspiracy movement, whose believers claim Trump is locked in a struggle with Democratic and Hollywood elites who practice child sex trafficking and cannibalism.

"QAnon is now painting Joe Biden not as a legitimate opponent but as part of this team of globalists who are intent on destroying America, not to be argued with but to be eliminated," added Muirhead.

Voting day

Election day in America is normally the culmination of months of rallies, public outings and handshakes, canvassing and live debates between the rival candidates. Media talking heads and polling serve as a chorus until television networks start to forecast results, declare key states and, finally, declare a winner.

In 2020, coronavirus affected the schedule at every stage. The Democratic and Republican parties’ national conventions went virtual or were scaled down. Trump's Covid-19 diagnosis meant there were two rather than three live debates with Biden. Criticism about the president conducting public rallies while infections soared completed a never normal campaign.

For all its variables, however, this year's race has one more unknown. Will the vote be fair?

The most immediate disinformation risk, according to NYU's Tucker, is Trump's repeated claims that mail-in ballots will lead to fraud and a "rigged" election.

Trump made the same allegation in 2016. Subsequent investigations showed no evidence to support his theory. But as president, and with more than 83 million Twitter followers, his ability to repeat the same message has an amplifying effect that can wear down the public.

"This is disinformation," said Tucker of Trump's tweets and public statements on the issue.

"There are problems with people not filling out their ballots correctly, there's problems with people getting their ballots late, but there is no evidence to suggest that there has been wide-scale fraud.

"The Russians were to the best of our knowledge the only ones meddling in 2016, and the platforms weren't prepared for it," said Tucker.

"But who needs the Russians running around casting doubt on the integrity of the democratic process when the president of the United States is doing it?"

What next for social media?

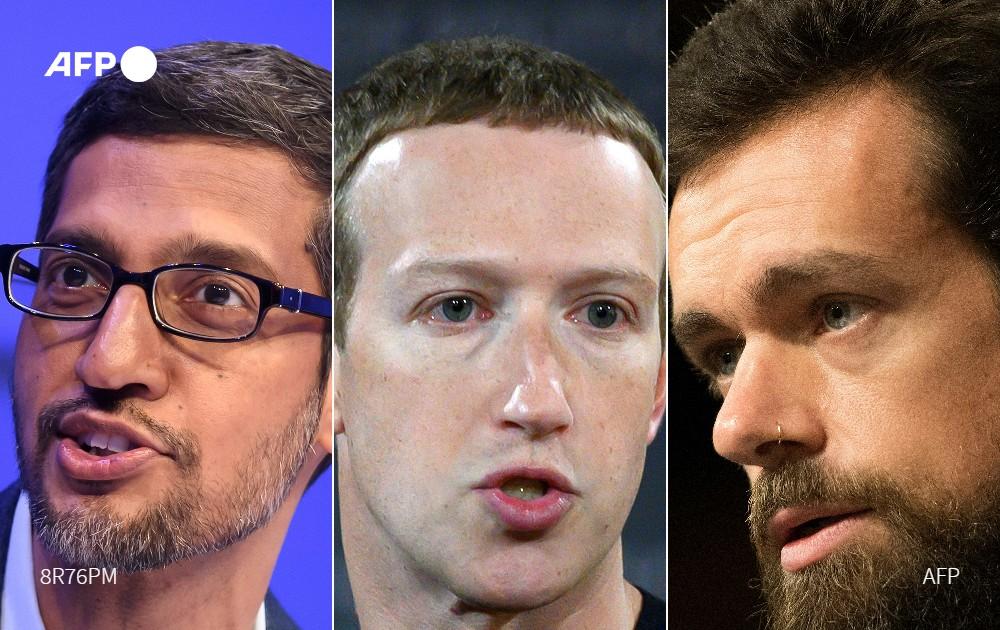

When the election ends, the battle over the future of social media will likely resume on Capitol Hill, where Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg, Twitter's Jack Dorsey, and Google's Sundar Pichai testified on October 28.

They defended Section 230 of the 1996 Communications Decency Act, their shield against legal liability over what users post on social media. But pressure for reform, a rare area of bipartisan agreement, is growing.

Do the companies agree to regulations that could jeopardize the freedom of expression that their business models rely on? Or do they fight governments and pressure groups that increasingly believe big tech has oversized influence on an internet driven by social media that at its worst is a supercharged delivery system for disinformation?

Neither side appears willing to give way.

"They can expect that many leaders will seek reform," Muirhead said of what comes after the election, noting that many of the concerns about content come from employees within the tech companies involved.

"They are worried that they will become synonymous with evil.

"It's not that we believe everything that we read. We can be skeptical. But repetition substitutes for validation in the new world of information. If Trump wins, we will face one future. And if he loses we will face another. It could be the beginning of the end of the politics of misinformation, or it could be the affirmation of the conspiracism that completes fabrication."

Attacks on voting by mail

The allegations looked plausible, featuring mail-in ballots addressed to dead people or former residents. But the claims posted on social media were inaccurate, and may have undermined confidence in the presidential election.

Donald Trump has repeatedly said that mail-in voting would lead to widespread fraud, encouraging similar claims on social media. But contrary to the president's assertions, undercounting poses a greater risk than overcounting, as ballots can be rejected if voters change signatures, or if they do not arrive on time.

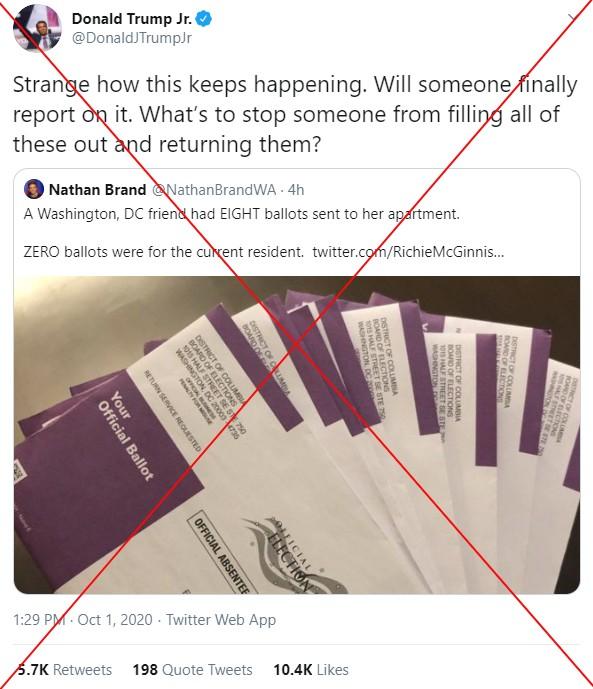

"Strange how this keeps happening," Donald Trump Jr, son of the president, wrote in a tweet, sharing a photo of eight mail-in ballots allegedly sent in error to an apartment in Washington, DC, adding: "What's to stop someone from filling all of these out and returning them?"

The answer is straightforward. The system contains safeguards such as signature verification -- done automatically by machine, or manually in some counties -- that experts say are proven to work.

But problems do occasionally arise. Other social media users have echoed the president and his campaign team, who say the election will be "rigged" because of large mail-in voting numbers for Democrats.

AFP looked into several cases across the United States.

Washington, DC

The tweet shared by Donald Trump Jr refers to another account that claims a friend received eight ballots, all of which were addressed to previous tenants.

This occurred because, in response to the pandemic, the DC Board of Elections (DCBOE) decided to automatically send mail-in ballots to registered voters, including to previous tenants who did not register their change of address.

But others would not be able to submit them in their place, said Nick Jacobs, a spokesman for the DCBOE.

"The simple answer is that it can't happen, we have a signature verification. If it’s not signed or the signatures don't match, it's not processed," Jacobs told AFP.

Voters can track their ballot on the DCBOE's website, and find out whether their signature has been accepted.

New Mexico

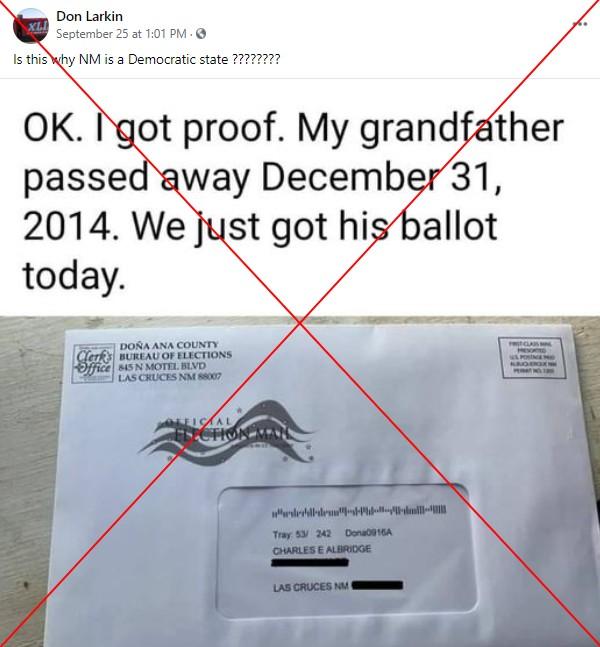

"I got proof. My grandfather passed away December 31, 2014. We just got his ballot today," text accompanying a photo of an envelope from New Mexico's Dona Ana County Bureau of Elections said in a Facebook post.

However, according to Dona Ana County clerk Amanda Lopez Askin, the envelope actually showed a mail-in ballot application, not an actual ballot.

"It's really unfortunate that rampant misinformation on a very innocuous application that is sent for voters' convenience is being used as a claim of voter fraud," Askin said.

Jack Mumby, deputy digital director for Common Cause, a watchdog group for democratic institutions, described problems such as old addresses as the expected glitches involved in any large-scale system.

"What some of this disinformation on social media has (done)... is they start a conversation that puts doubts in people's heads about the integrity of our elections, and there are political actors who seek to exploit that for political ends," he said.

"Mail-in ballots are safe, secure, and tested, and sadly some people see political opportunity in undermining that confidence. Once that narrative is out there, what could be a small scale bureaucratic mix up becomes confirmation of that narrative."

Wisconsin

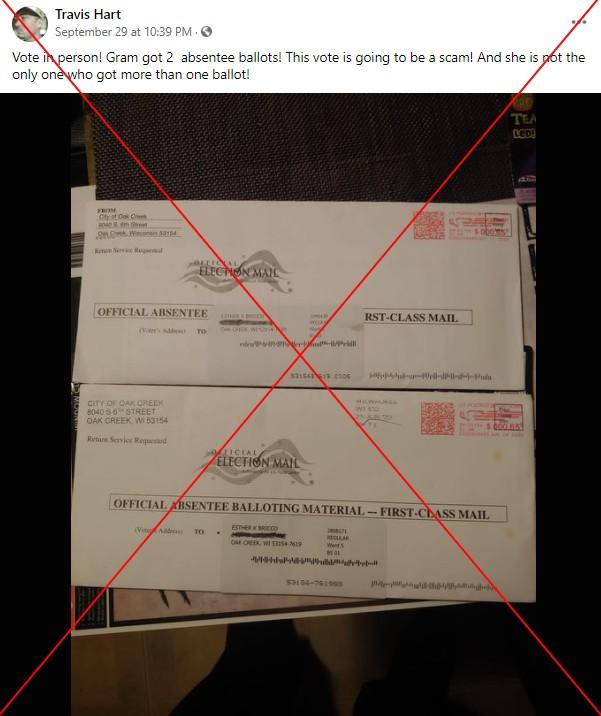

Another Facebook post alleged that a woman in the Wisconsin city of Oak Creek had received two ballots for the November 3 election. The Facebook user advised everyone to "vote in person" because "this vote is going to be a scam!"

But the photo actually showed a ballot for the November general election as well as one for the August primary, Oak Creek city clerk Catherine Roeske said.

The date on the bottom envelope in the photo was from June 2020.

"We didn't even have ballots for this (November 3) election until the 17th of September so… busted," Roeske said. "This is how rumors get started."

Theodore Allen, an associate professor of engineering at Ohio State University who has worked on election projects, said the main problem exposed so far was undercounting, because a voter's signature can change over time.

"The biggest challenges to my mind relate to discouraging voters, including through making registration unnecessarily difficult, insecure voter registration rolls, and laws and practices targeting minorities," he said.

New Jersey

Some residents of the Garden State complained about receiving ballots not addressed to them, or to deceased relatives.

One man in Mercer County said he received two mail-in ballots for his parents, who had died eight years ago. Another complained about receiving one for his mother-in-law who died five years ago, and a third said he got one for a woman who had been dead 17 years.

Unlike the New Mexico case, the ballots in those photos were proper mail-in ballots, not applications. "I've seen the same story all over the state," said Mercer County Clerk Paula Sollami Covello.

These situations occur "because the registration offices rely on getting a letter notifying them someone's passed away," she said. Those deceased individuals were always registered as voters, "but it's only this year that it was discovered because we were mandated to send everybody a ballot."

In prior years, New Jersey residents would have had to request a mail-in ballot, but in light of the pandemic, an executive order by Democratic Governor Phil Murphy required election officials to automatically send ballots to all active registered voters.

Covello, who has administered New Jersey's mail-in voting since 2009, says these errors don’t threaten the integrity of the vote. "It's worked out very well for us, we've seen very little instance of fraud."

She said that ballots received for deceased individuals should be returned to the sender with the word "deceased" written on the envelope.

Kimberly Burnett, spokeswoman for New Jersey's Middlesex County government, said forged signatures on returned ballots "will be flagged by Board of Elections staff when researching signatures."

"A flagged ballot will be referred to the county prosecutor for election fraud if our office determines a voter is deceased through a post-election audit," she said.

Fauci politicized, targeted with disinformation

Anthony Fauci, America's top infectious diseases expert, prides himself on steering clear of politics.

But with unrivaled credibility on the novel coronavirus that both Donald Trump and Joe Biden were eager to associate with their campaigns, the scientist was pulled into the closing stage of their battle for the White House.

Just weeks before election day, the Trump campaign released an ad that misleadingly used months-old footage of Fauci to portray him as praising the president’s actions on the pandemic. This prompted the 79-year-old doctor to issue rare public criticism of a move by Trump that in turn was seized on by Biden.

The ad was not the first time that Fauci’s words or actions were misrepresented during the pandemic: the longtime head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases has been repeatedly targeted with disinformation on social media during the course of the crisis.

Fauci became a revered figure on the left while facing widespread criticism from the right over the course of 2020, and politicians from both major US parties sought to make use of his reputation.

He successfully navigated this political minefield, largely avoiding direct criticism of Trump, whose relentless optimism about the coronavirus contrasted with his straight talk aimed at highlighting health dangers to the public. But the final stretch of the 2020 electoral campaign posed a unique challenge.

"It's frustrating to him to see himself be politicized, when he spent... 40 years not being political and trying to avoid that issue," Zeke Emanuel, chair of the Department of Medical Ethics and Health Policy at the University of Pennsylvania, told AFP.

Asked why Fauci's endorsement was so sought after, Emanuel said: "Integrity and credibility -- it's just that simple. The man has integrity, he says what he sees in the science, and therefore he has credibility."

'Last-ditch effort’

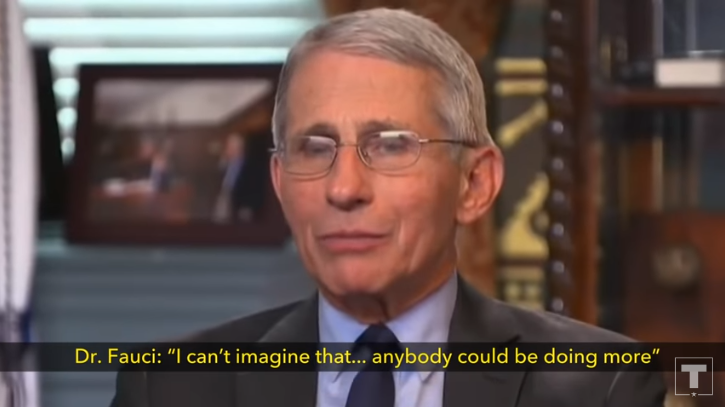

In the Trump ad, a narrator says that, "President Trump tackled the virus head on, as leaders should." It then cuts to a clip of Fauci saying: "I can’t imagine that... anybody could be doing more."

Fauci hit back, saying that, "In my nearly five decades of public service, I have never publicly endorsed any political candidate."

He also criticized the ad for taking his "broad statement" on federal health officials out of context -- an assertion backed up by his full remarks in a March 2020 interview on Fox News, a portion of which was used in the ad.

Trump campaign communications director Tim Murtaugh stood by the ad. "These are Dr Fauci's own words," he said. "The words spoken are accurate, and directly from Dr Fauci's mouth."

The dispute did not end there.

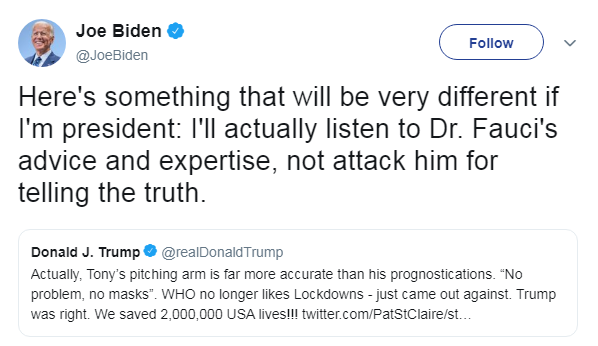

Fauci said on CNN that he thought the ad should be pulled, while Trump referenced the doctor's errant Major League Baseball opening day pitch to criticize him on Twitter: "Tony's pitching arm is far more accurate than his prognostications."

The president subsequently took aim at him on a call with his campaign team, saying: “People are tired of hearing Fauci and all these idiots.”

"He's been here for, like, 500 years," Trump said, adding without evidence that “if we listened to him, we'd have 700,000 (or) 800,000 deaths.”

Todd Belt, director of the Political Management Program at George Washington University's Graduate School of Political Management, said of the ad: "This was a last-ditch effort to burnish Trump's credentials on how he's handled the pandemic."

He "was apparently trying to harness Fauci's popularity," Belt said.

Fauci has at times spoken positively about the US coronavirus response in general, and Trump's actions specifically.

The Trump campaign used such remarks to defend the president's coronavirus record, such as with a list posted on the campaign's website that contrasts the doctor's statements with criticism from Biden.

Target of disinformation

"DR FAUCI HAS REPEATEDLY SAID THE TRUMP ADMINISTRATION DID EVERYTHING POSSIBLE TO SAVE LIVES," the list's title says.

The politicization of Fauci also occurred on the left, though not on the same scale.

Biden criticized Trump for allegedly not listening to Fauci. And his Democratic running mate Kamala Harris contrasted her trust in the doctor with her lack of faith in Trump when it comes to a coronavirus vaccine during the recent vice presidential debate.

Biden also seized on the ad controversy, tweeting that, "Donald Trump is running TV ads taking Dr. Fauci out of context and without his permission."

"Here's something that will be very different if I'm president: I'll actually listen to Dr. Fauci's advice and expertise, not attack him for telling the truth," the Democrat wrote on Twitter in response to Trump’s tweet about Fauci’s pitch.

Trump's remarks about Fauci on the campaign call provided another opportunity for Biden to criticize the president.

Trump "decided to attack Dr. Fauci once again, calling him a 'disaster' and public health experts 'idiots.' Meanwhile, he still has no plan to beat this virus," the Democrat tweeted.

In addition to politicians' efforts to make use of Fauci's reputation, the doctor also faced repeated efforts to defame him on social media in 2020.

A misleading video viewed more than 2.5 million times on Facebook, for instance, used footage of Fauci to question his judgment and criticize face mask recommendations aimed at curbing the spread of the coronavirus.

Other posts on the social media site falsely said a photo showed Fauci making a 2015 visit to a laboratory in China's Wuhan, which later became ground zero for the coronavirus pandemic.

But Trump's ad -- and its direct politicization of Fauci -- posed a different kind of challenge to the doctor, and he publicly pushed back.

For Trump's team, the ad effort "backfired" because of Fauci's response, said Belt.

It reinforced "the notion that Trump is only interested in himself and his electoral fortunes, not the country at large, as a leader should be," he said.

Manipulated media thrives in 2020 campaign

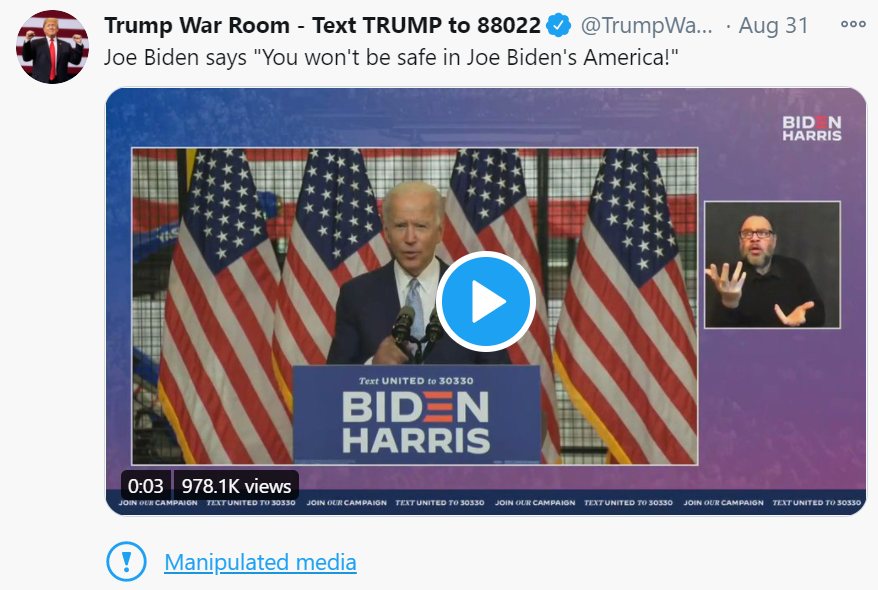

A message saying you "won't be safe" in Joe Biden's America. The former vice president shown "sleeping"during a television interview. Biden "hiding"-- alone -- in his basement.

All three videos featured in social media of President Donald Trump and his team as he sought to close the gap on his Democratic rival in the summer. And each was labeled as false or manipulated content by social media giants and fact checkers.

While negative campaigning has long been a fixture of American politics, the open use of digitally-altered images by Trump and other candidates in 2020 caused unusually firm reactions from tech giants.

Twitter cracked down by removing or labeling several of the president's tweets. Facebook, citing the risk of civil unrest, forbade new political ads on its platform in the last week of the November 3 race.

There remain questions whether such campaign messages -- almost impossible to stop once they become viral -- work on voters, but a line had already been crossed.

"There's a long tradition in politics of competing politicians presenting their opponents' words or beliefs in edited ways, right? That's part of politics," Ethan Porter, assistant professor of media and public affairs at George Washington University, told AFP.

On the other hand, he said, the Trump team was in part "running a campaign entirely detached from reality, in ways that have little to no precedent in American political history."

Biden's campaign did not receive the same kind of censure as Trump's. But can a willingness to manipulate highly visible political ads and videos produce results?

‘One-sided’

"Manipulated media for the most part has been used by the Trump campaign to try and have more, let's say, 'tactile-looking' evidence, for the claims that they're making. Because there's not actual evidence," said Shannon McGregor, an assistant professor at the Hussman School of Journalism and Media, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

It was similar to the approach used in 2016, but technology has made manipulations easier and more sophisticated.

Asked about the Biden videos, the Trump campaign accused tech companies of double standards.

"Big tech is in Joe Biden's pocket but the liberal coastal elites in Silicon Valley are blatantly one-sided when it comes to how they define manipulated media," Samantha Zager, deputy national press secretary, told AFP.

However, McGregor, who studies the role of social media in political processes, said that rather than aiming to attract different constituencies, "the rhetoric is really polarizing and it's sort of digging into Trump's base of supporters and trying to activate them to vote."

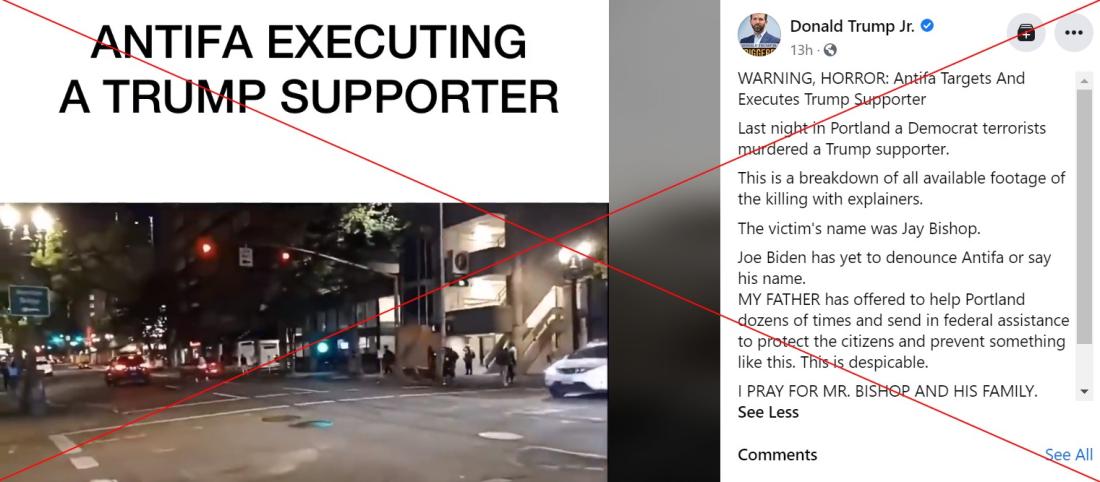

An example came in an August 30 Facebook post by Donald Trump Jr, after the shooting death of Aaron Danielson, 39, in Portland, Oregon.

"WARNING, HORROR: Antifa Targets And Executes Trump Supporter," the president's eldest son said in his post, which included video that was viewed more than 780,000 times, and liked almost 50,000 times.

A suspect said to be a supporter of the Antifa anti-fascist movement was shot and killed as police tried to arrest him.

'Drinking their Kool-Aid'

The violence in Portland came just before Facebook boss Mark Zuckerberg announced the restrictions on political ads, saying misinformation about mail-in voting, and concerns about delayed counting of ballots, meant the 2020 election was not business as usual.

Porter said the Trump team was convinced its approach was a winner.

"In some ways they seem to have drunk their own Kool-Aid. They believe that their social media use and strategy in 2016 won them the election," he said.

“It's not to say he won't win. It's just to say that if he does win I can't imagine that will be one of the top or most likely causes," Porter added during the campaign, maintaining that fact-checking of false information does work.

Cyrus Krohn, who managed digital campaigning for the Republican National Committee ahead of the 2008 election, said in a September 2, 2020 interview with AFP that the presidential race did "appear to be tightening" after the use of manipulated media. "You can attribute that to the fear factor that the internet is creating," he said.

And although the Biden campaign was not "as overt," Krohn said, "there are factions on the left who would like to see the (former) vice president elected that are deploying the same tactics as the official Trump campaign."

Story design by Marisha Goldhamer

Copyright © AFP 2017-2026. Any commercial use of this content requires a subscription. Click here to find out more.

Is there content that you would like AFP to fact-check? Get in touch.

Contact us