How we work

Investigating viral, harmful misinformation

AFP’s fact-checkers seek to investigate dubious claims circulating online which are viral, impactful and potentially harmful to the public. The claims we verify surface in a variety of ways, including on social media platforms, blogs and websites, messaging apps and other forums in the public sphere.

We identify claims we want to investigate by assessing whether a fact-check would be in the public interest and whether we would be able to gather clear and sufficient evidence to disprove the specific claim or claims being made. AFP fact-checking teams verify facts, not opinions or beliefs. If we are unable to establish strong and cross-checked evidence, we will not publish a fact-check.

We pay particular attention to misinformation that could endanger people's health or lives, damage democratic processes, or promote hate speech and racism.

We apply the same investigative approach and standards of evidence regardless of who has made the claim, and we do not focus on any one candidate, party or website. We may however produce more fact-checks on sources that are consistent spreaders of potentially harmful misinformation. You can read more about the ethical standards that uphold AFP’s commitment to impartiality and independence here.

Open sources

Our fact-checks are based on non-partisan, primary-source material gathered by our fact-check journalists, including material verified via AFP’s own archives and collaboration with the agency’s on-the-ground reporters around the world. We also talk to experts and quote them in our fact-checks, identifying who they work for, what their area of expertise is and any conflicts of interest they may have. We require at least two independent sources of information to verify the central claim of a fact-check.

We aim to transparently show the steps we take throughout the debunking process by including links, embeds, screenshots, photographs and archived evidence that we have used to reach a conclusion. Our goal is for readers to understand how the investigation was carried out and to be able to follow the same steps themselves.

As a general rule, AFP does not use anonymous sources in its fact-checks. There may be exceptional cases where a source’s safety is at risk and the information they have provided is both necessary for the debunk and has been corroborated by other open sources.

If any element of a claim under investigation is true, we acknowledge that in our fact-checks, supported by evidence.

Tools and approaches

We use traditional journalism skills and a number of simple tools, some common sense and a lot of caution.

For example, if we believe an image has been manipulated or presented out of context, we search for the original image and try to speak with the photographer or subject to find out more about it. If we are looking at a claim that presents data to back an argument, we will search for the original source and talk to experts for their informed views about the statistics presented in the claim.

We use archive tools, such as Wayback Machine or Perma.cc, to avoid increasing clicks on false information and to keep a record in case a post later changes or vanishes. We thus archive both false claims and evidence links, whenever possible.

Below is a run-through of the methods we regularly use in our debunks:

Searching for images

A great deal of false information involves old images taken out of context.

To trace the source of an image, we start with a reverse image search, inserting the picture in one or several search engines to see if it has previously appeared online.

A right click on a picture in the Google Chrome browser gives the option "search image with Google". The search engine will trawl its database to see if there are similar images in its index.

We regularly use and recommend our InVID/WeVerify extension, which gives you a choice of image search engines including Google, Bing, Yandex, TinEye and Baidu, with a simple right click on an image once you've installed the extension.

Reverse search does not always give results, either because an image has never been published on the internet, or because it has not yet been indexed. Sometimes, reverse image search engines can be confused by an image that has been flipped around, such as the one we encountered in this story about a former Japanese prime minister.

We therefore also observe visual clues (such as shop signs, street signs, architecture, vegetation, licence plates) to find the location or date of an image.

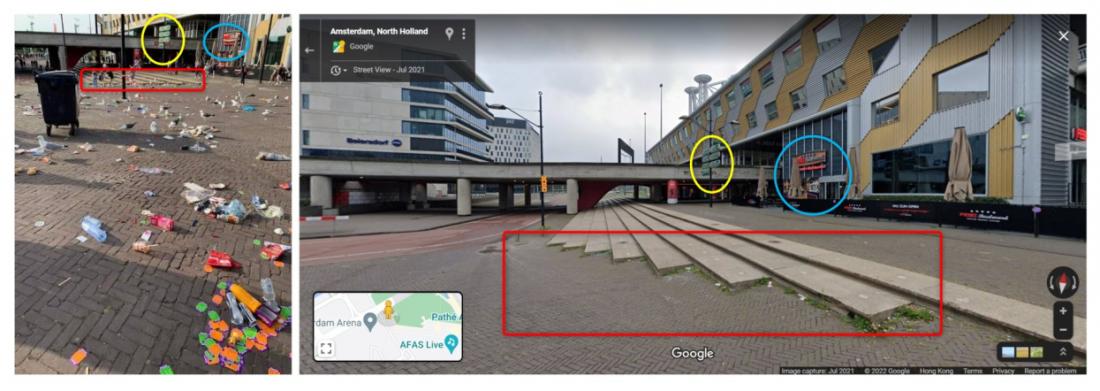

For example, as seen below, we confirmed the location of a photo taken in the Netherlands for this investigation by comparing architectural details and signs in the photo (left) with Google Maps Street View (right).

Images or videos alone are usually not sufficient proof of a claim. We also need to check the coherence of an image with information such as the date it was published and details within it, such as weather conditions.

When dealing with suspect images, we try our best to obtain the original files to determine if they have been altered.

Investigating videos

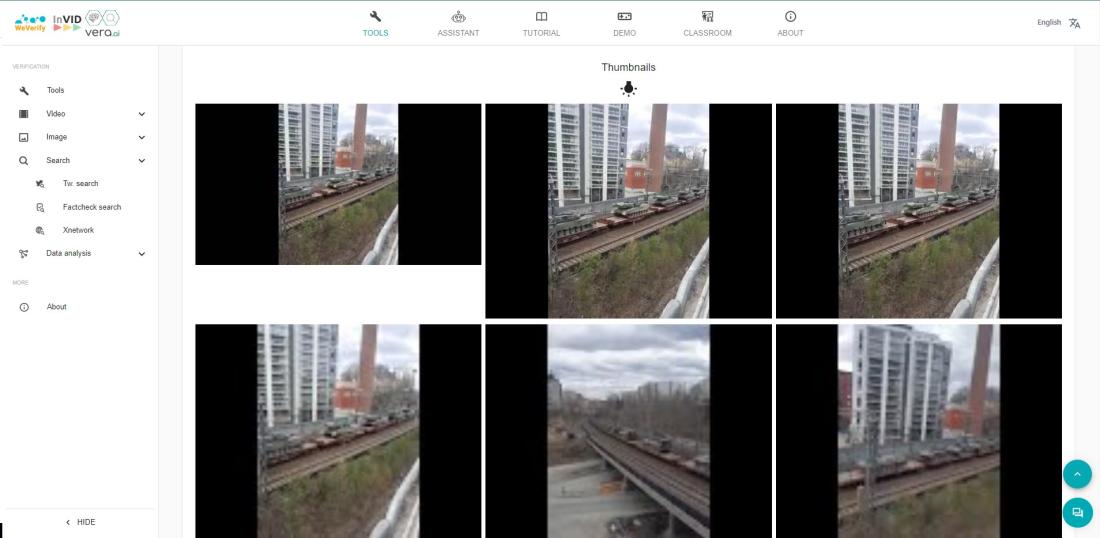

To analyse videos, we also use the InVID/WeVerify extension, which was co-developed by AFP. The tool allows us to cut a video into thumbnails and then carry out several reverse searches on the images.

It also can be a great help if you suspect an image has been flipped around, as the extension allows you to flip it back.

Searching for and verifying comments and data

A simple copy and paste of a paragraph of text into a search engine can often reveal if it has already circulated online.

If a comment is attributed to a person, we seek a reliable source (audio or video recording, official transcript), as well as looking at the person's online accounts for further verification. We will also contact the person directly to seek to confirm their statement.

When dealing with quantitative data, we look for the original study and its methodology and speak with experts who are either the authors of the original study or experts with a track record of research in the same field to verify whether the data is being misrepresented in the claims under investigation.

We regularly deal with topics on which we have little previous knowledge. In these cases, we collaborate with AFP journalists with expertise in a specific subject, region or language. We work closely with AFP's worldwide fact-checking team to verify aspects of claims that may relate to other regions.

AI-generated content

As with every new technology, artificial intelligence (AI) is providing new tools and new challenges. It is increasingly difficult to verify AI-generated content even though much of our verification work still centers on less sophisticated techniques of falsifying information.

AFP has internal guidelines on how to handle AI-generated content. These guidelines are updated regularly due to the rapid evolution in this field. We cannot use evidence from an AI-detection tool on its own and we must always carry out other checks too (e.g. reverse image search, etc.). More detail on how we approach artificial intelligence can be found in AFP’s Editorial Standards and Best Practices and in our Fact-Checking Stylebook.

Cross-checking information

If a claim circulating on the internet appears doubtful - especially if it does not cite a source - one of our first reflexes is to study the comments. Some might provide contradictory information or raise questions about the veracity of a post.

If a person or organisation is mentioned, we contact them for their version of events. When appropriate and possible, we contact the source of the claim under investigation to seek further information.

If a questionable publication is based on a picture or video, we will search for other images from the same event to compare them with. We also seek to contact the author of the image for more information.

Not just the internet

For some fact checks, the internet and telephone are not enough. Sometimes - as in all journalism - you need to be in the field. When something can be verified in person, we send our reporters to investigate with their own eyes and ears. We also work closely with AFP journalists who are covering news around the world.

For this article in April 2024, for example, we verified a video that showed military vehicles on a road near a construction site. The caption identified them as French armored vehicles that had arrived in the Ukrainian city of Odesa during the conflict between Russia and Ukraine. We used open source information available online to verify the origin of the video and the country to which military vehicles with those markings might belong. With these tools we were able to establish that the video was filmed in Poland. We identified an electoral campaign poster in the images, which enabled us to narrow down the location to a specific town. Colleagues in AFP’s bureau in Warsaw, Poland contacted local officials in the town and people involved the election campaign were able to provide a photo of the exact location where the video was filmed. This proved that the video was indeed shot in Poland, not in Odesa as the social media post had claimed.

Editing and ratings

Our journalists liaise with regional editors throughout the process of producing a fact-check. Editors discuss claims and proposed fact-checks with journalists, assess and explain what evidence will be needed, and edit the article before publication.

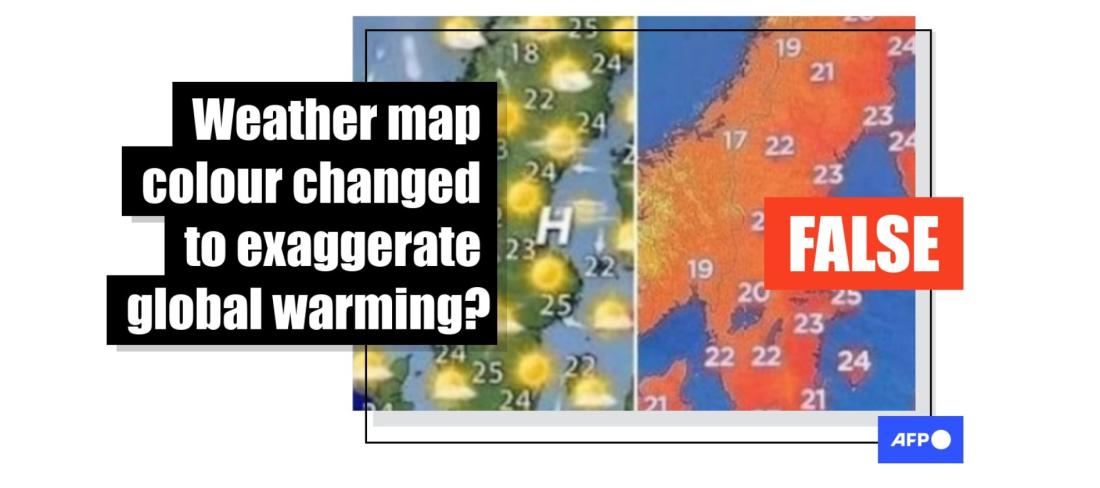

Fact-checks published on AFP’s websites carry a rating to indicate to readers the conclusion of each investigation. The rating is either part of the header image at the top of the article, as shown below, or explained in the introduction of the fact-check.

The terms that we use include:

- False - We state an item is false when multiple and reliable sources disprove it.

- True - We state an item is true when multiple and reliable sources have confirmed the information to be authentic.

- Misleading - We state an item is misleading when it includes genuine information (text, photo or video) that has been taken out of context or is mixed with false context.

- Altered Photo - When a photo has been manipulated to deceive.

- Altered Video - When a video has been manipulated to deceive.

- Missing Context - When a claim has some element of truth but might be deceiving without further information.

- Satire - When a claim is false and has the potential to fool but may not have originally been intended to deceive (e.g., humour, parody).

- Hoax - When an image or incident has been fabricated.

- Deepfake - When a video or audio recording has been manipulated using artificial intelligence to create fabrications that appear real.

More details about our fact-checking process and editorial guidelines can be found in AFP’s FactChecking Stylebook.

Partnerships with online platforms

Meta programme

As part of Meta's Third Party Fact-checking programme, we consider posts flagged on Facebook and Instagram as part of the material we investigate, and our fact-checks appear on posts that we have rated as false, partly false or missing context.

TikTok programme

As part of TikTok's Global Fact-checking programme, we consider videos posted on TikTok as part of the material we investigate, and our fact-checks contribute to the in-app moderation process. We also investigate TikTok content as part of the content we tackle in the fact-checks we publish on our websites.

Our fact-checking teams in Brazil, Mexico, the United States (in Spanish), India, Germany and France operate WhatsApp tiplines through which the public can submit possible claims for investigation.

Claim Review tool

AFP uses the Claim Review tool in its fact checking articles. This allows search engines, such as Google and Bing, to easily present fact checks in response to searches for specific claims.

More details about our partnerships and funding can be found here.