How anti-China disinformation shaped South Korea's year of crisis

- Published on December 3, 2025 at 09:59

- 7 min read

- By SHIM Kyu-Seok, Hailey JO, AFP South Korea

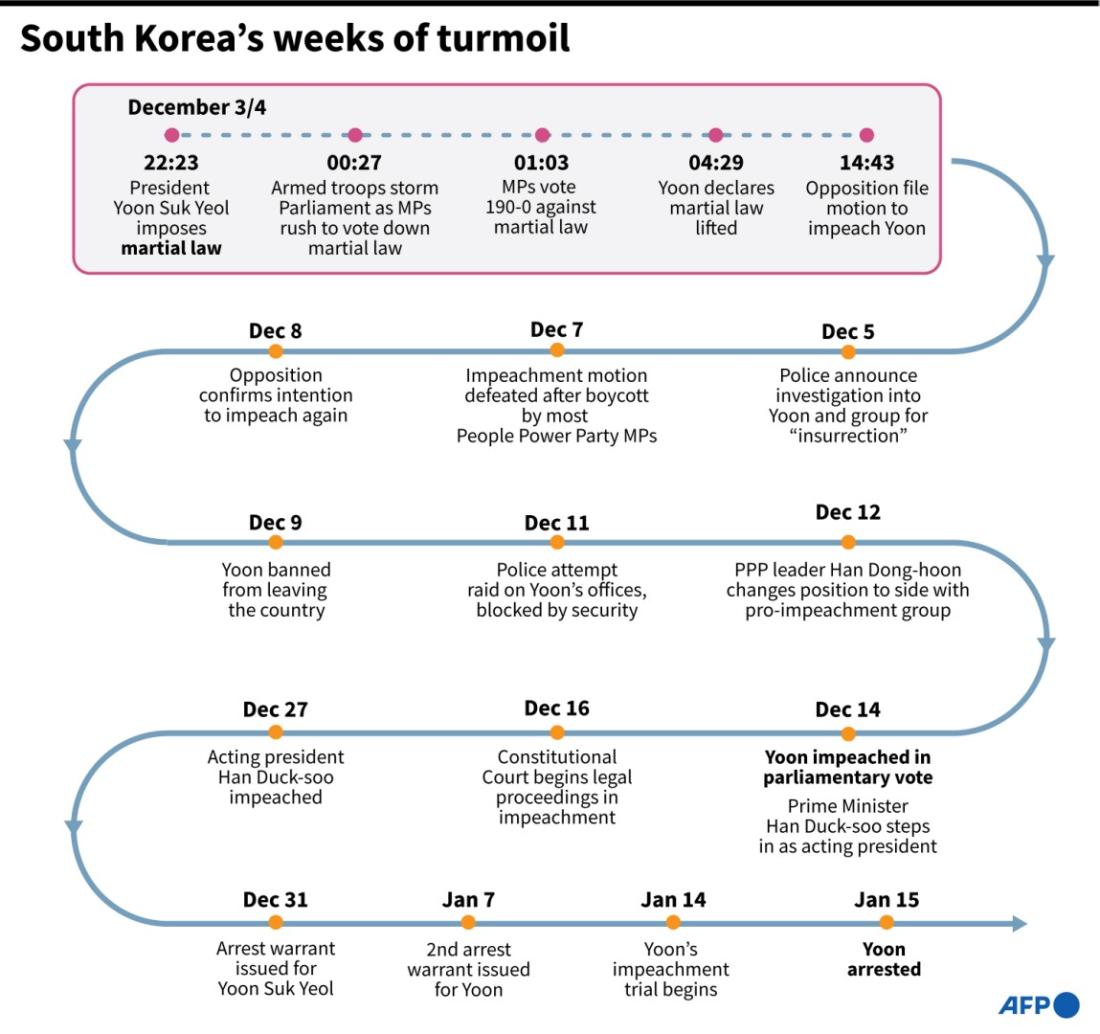

When former president Yoon Suk Yeol tried and failed to impose martial law in December 2024, South Korea plunged into its worst political crisis in decades. Yoon's impeachment and the ensuing chaos provided fertile ground for disinformation to grow in a country already entangled in conspiracy theories.

A common refrain, posted on right-wing forums, amplified by popular YouTubers and echoed by lawmakers at rallies: China was to blame.

Yoon supporters and sympathetic politicians alike claimed Beijing had infiltrated protests, funded his impeachment campaign and manipulated online opinion ahead of the June snap election that brought opposition leader Lee Jae Myung to power.

Yoon himself fuelled the suspicion in December 2024 during televised remarks defending his failed martial law decree, warning that "forces linked to North Korea and China are threatening our democracy from within."

But an AFP Fact Check review of the most widespread claims about Beijing's influence on South Korea's political upheaval this year, including alleged "spy arrests" and rumours of Chinese-backed protests, found no solid evidence to support them.

Instead, experts say the narrative was a homegrown reflection of domestic political rivalries and long-simmering anti-China sentiment.

"There used to be goodwill toward China, a sense of economic partnership," said Ha Nam-suk, a professor at the University of Seoul (archived link).

"But as competition deepened and cultural disputes intensified, frustration turned into resentment. Politicians understood that, and some used it as a convenient rallying tool."

Anger over China's purported meddling spilt over into the streets of Seoul throughout August and September, where small right-wing groups waved flags and chanted slogans against "Chinese infiltration" (archived link).

Surveys show Koreans' negative perceptions of China have deepened over the past year, while Chinese nationals and residents in Seoul say they've faced a growing tide of discrimination and harassment (archived link).

AFP examined the origins of the disinformation onslaught that helped define the past year of South Korean politics.

'99 Chinese spies'

The first wave hit in January, shortly after Yoon's impeachment (archived link). Right-wing YouTubers such as Shin In-kyun claimed "99 Chinese spies" had been arrested at the National Election Commission (NEC) and flown to Okinawa by the US military.

Users on fringe forums such as Ilbe and DC Inside soon picked up the story. Then it was reprinted by the conservative media outlet Sky eDaily and circulated widely on Facebook.

AFP found the corresponding photos were taken in 2016 and show Chinese fishermen detained for illegal fishing. Both the NEC and US Forces Korea said the reports were "entirely false" (archived here, here and here).

Still, the claim spread rapidly through pro-Yoon networks online. Yoon's lawyer later mentioned it before the Constitutional Court.

"Younger Koreans already had strong resentment toward China over cultural and historical issues," Ha said. "After Yoon's impeachment, online influencers weaponised that resentment, turning frustration into political identity."

Later, a video showing dozens of social media dashboards running on one screen circulated on X and Facebook with the caption: "Chinese AI bot farm manipulating Korean opinion."

AFP traced it to a developer demonstrating an AI agent named Manus, not a state influence campaign (archived link).

But with the country's impeached leader warning of "foreign interference," the clip fit a convenient storyline.

Courts and conspiracies

By February, attention turned to the Constitutional Court, which was considering Yoon's removal. Justice Moon Hyung-bae, the top judge overseeing the verdict, was targeted by a doctored image showing him "swearing allegiance before a Chinese flag."

The original Yonhap photograph showed South Korea's flag (archived link).

Moon continued to face disinformation and threats, and when the Court unanimously voted to oust Yoon in April, the rumour gained traction among supporters who believed the judiciary itself had been "compromised."

Several surveys conducted early this year indicated public distrust in the court had risen beyond 40 percent.

Some pro-Yoon protestors violently stormed a different court responsible for issuing Yoon's arrest warrant in January, their anger stoked by a growing conviction that the justice system was part of an elaborate political conspiracy (archived here and here).

Anti-Yoon protests also became the target of online falsehoods, with posts in multiple forums zeroing in on a Chinese-language poster seen in central Seoul after the president's removal from office.

AFP geolocated it to Gwanghwamun Gate, where Korean demonstrators put it up to inform tourists about ongoing protests against Yoon. The text's awkward phrasing and accompanying English, Thai and Japanese versions showed it had been translated from Korean (archived link).

Yet online, it was repurposed as "proof" that China had orchestrated Yoon's downfall.

'Chinese influence'

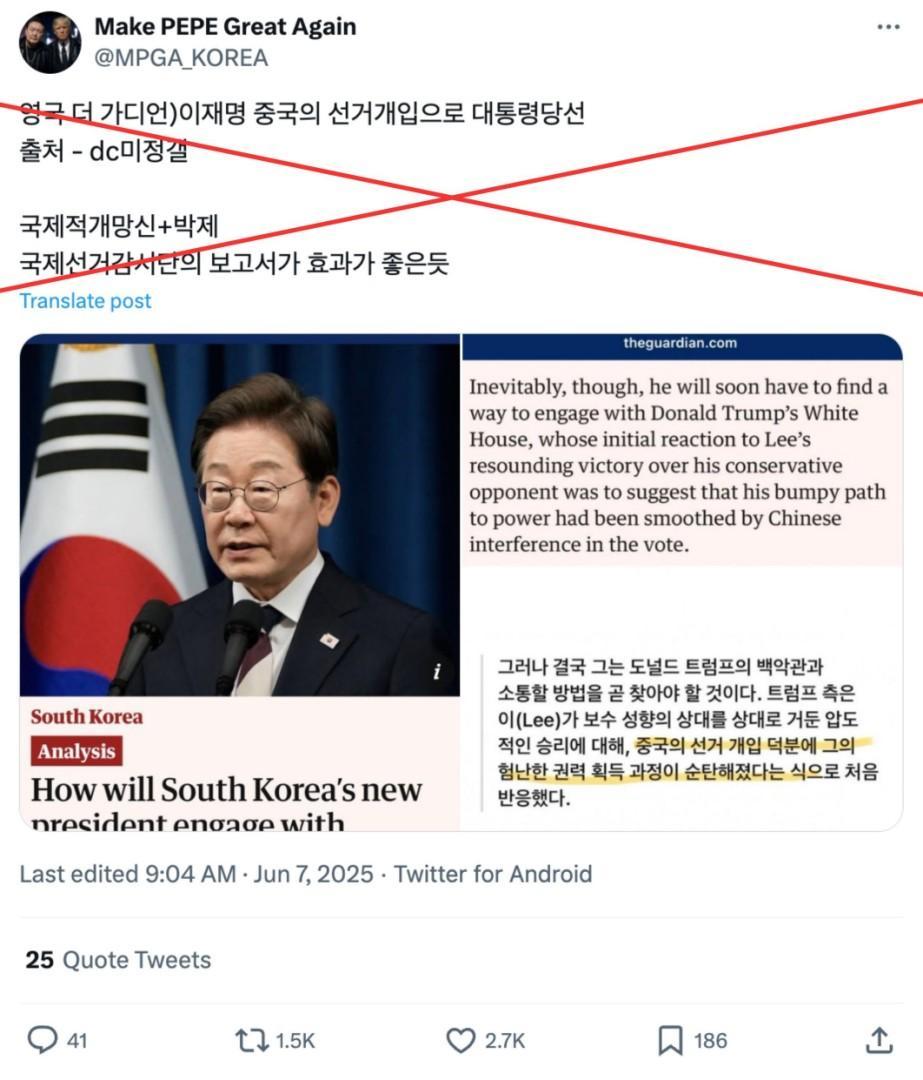

When opposition leader Lee won the June 3 presidential election, the same anti-China themes that had been brewing all year resurfaced. Posts on X, Facebook and Threads falsely claimed The Guardian reported that China helped Lee win (archived link).

In fact, the article in question merely cited a White House official's broad concern about Chinese influence in democracies worldwide -- without referring to South Korea's vote (archived link).

The distortion resonated across right-wing spaces, merging resentment over Yoon's removal with suspicion of Lee's perceived openness to dialogue with Beijing.

One post from Yoon ally and People Power Party lawmaker Yoo Sang-bum claimed Chinese nationals "heavily participated in pro-impeachment rallies" (archived link).

Another from right-wing YouTuber Shin said the election "proved how deeply Chinese influence runs in our politics."

Both assertions were baseless, but they drew tens of thousands of interactions across Facebook and YouTube.

"Once those stories took hold, they became symbols of something larger," said Kim Hee-gyo, a professor at Kwangwoon University (archived link).

"You see banners from far-right groups and even some opposition People Power Party figures using identical language -- that kind of coordination doesn't happen by chance."

Visas and voter fraud

In the second half of 2025, disinformation shifted to immigration policy.

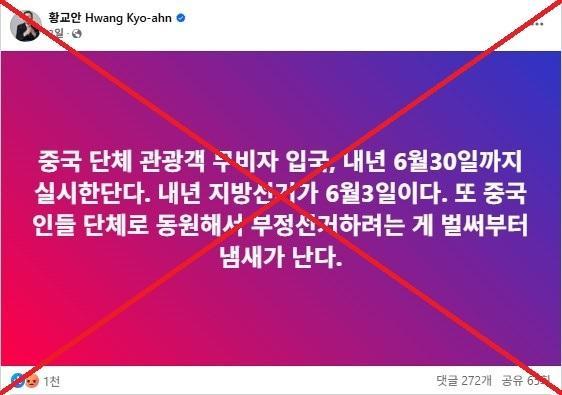

When the Justice Ministry introduced a visa-free program for Chinese group tourists ahead of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit, former prime minister Hwang Kyo-ahn claimed it was a plot to enable election fraud (archived link).

"The local elections next year are on June 3," Hwang wrote on his Facebook page. "I can already smell (the ruling party's) plan to commit election fraud by mobilising Chinese people en masse."

The NEC quickly clarified that only foreigners with at least three years of permanent residency can vote in local elections, making such fraud impossible. But soon after, a new rumour spread that all Chinese nationals could enter South Korea without passports or health checks.

The Justice Ministry called that "completely false," saying group lists are pre-screened and health surveillance remains mandatory.

Kim said that with Yoon no longer a viable focal point, hard-liners needed a new rallying cry.

"They filled the vacuum by constructing an external enemy, turning general anti-China feeling into ideological sinophobia," he said.

Ha drew a parallel to similar patterns elsewhere.

"When you see protesters in Seoul shouting at Chinese residents, it feels chillingly familiar," he said. "This isn't just a Korean problem. Across democracies, we're watching crusade-style politics take root -- where one side must die for the other to survive."

Copyright © AFP 2017-2026. Any commercial use of this content requires a subscription. Click here to find out more.

Is there content that you would like AFP to fact-check? Get in touch.

Contact us