Ahead of COP30, climate skeptics misuse study on Amazon forests

- Published on October 16, 2025 at 23:28

- 4 min read

- By Gaëlle GEOFFROY, Manon JACOB, AFP France, AFP USA

Climate skeptics are targeting new research on the Amazon to downplay global warming's impact on rainforests as Brazil prepares to host the annual United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP30) in Belém in November 2025, but experts -- including the authors of the paper -- say the claims are misconstrued.

The September 25, 2025 paper, titled "Increasing tree size across Amazonia," was published in Nature and covered across scientific outlets (archived here).

Over a period of 30 years, researchers from some sixty universities around the world monitored changes in the Amazon rainforest across 188 permanent plots and observed a 3.3 percent increase in the average size of tree trunks per decade, along with a noticeable rise in both the number and size of the largest trees.

The researchers concluded that the increase in atmospheric CO2 is the most likely -- though possibly not the only -- factor explaining this phenomenon.

Among climate skeptics, the paper's takeaway fueled online discourse that dismissed the impact of human-driven climate change on forests, particularly in French and Spanish (archived here). The carbon fertilization effect is a frequent topic of misinformation (archived here).

But three study authors, as well as independent scientists who spoke to AFP, said those claims misinterpret the climate stressors existing in the region, where world leaders will gather for UN climate talks in November.

Corresponding author Becky Banbury Morgan, a research associate at the University of Bristol, told AFP October 1 that the research's conclusions about trees and CO2 do not disprove the impacts of warming in Amazonia (archived here).

"This paper shows how these forests have changed over the last decades, but we don't know what will happen in the future or if this growth will continue," she said, adding that the research was observational and not based on experimental tests (archived here).

Co-author Adriane Esquivel Muelbert of the University of Birmingham concurred, saying October 1 that it "is extremely likely that with greater atmospheric CO2, leading to greater temperatures and extreme weather, these forests would be greatly affected" (archived here).

Roel Brienen, another co-author from the University of Leeds, told AFP on October 9 that the study "is certainly not a call to say that CO2 is good and that we still need a 'bit more of it' simply because plants use it" (archived here).

Forest remains vulnerable

Scientists say there are many existing and future climate-related threats to the Amazon.

Higher CO2 concentrations due to climate change accelerate drought episodes in the region, which impacts trees (archived here).

The Amazon is facing record-breaking droughts, said Carlos Nobre, an Earth system scientist at the Institute of Advanced Studies at Brazil's University of São Paulo (archived here).

"In the future, these negative impacts may outweigh any positive effect of CO2 fertilization, so we have to keep monitoring these forests into the future to see how they will respond," Banbury Morgan told AFP.

Bernardo Flores, a scientist at the Federal University of Santa Catarina in Brazil, added that the Nature paper left room for potential misinterpretation by omitting "key factors" (archived here).

"The conclusion that CO2 fertilization is causing the observed increases in large-tree abundance across Amazonia is purely hypothetical," he said October 9. "This would require experimental tests and modeling."

"While CO2 (levels) may indeed fertilize tropical forests, they could also increase tree mortality and carbon emissions," he said.

University of Leeds's Brienen agreed, noting that the same timeframe has also seen tree mortality rates in the Amazon "going up."

He said CO2 fertilization could also reduce a process known as forest transpiration -- whereby trees transport water from the soil to their pores, creating vapor that has a local misting, cooling effect -- across the Amazon, "making the system as a whole less resilient" (archived here).

Current and projected changes in the composition of the Amazon forest due to carbon emissions have been highlighted by several studies, including some by the same authors as the research in question (archived here).

Deforestation and fires

Amazonia also faces the threat of deforestation, primarily driven by agriculture and infrastructure development.

Using data collected over 40 years from 1985 to 2024, the monitoring network Mapbiomas determined that the Amazon has lost an area roughly the size of Spain or the state of Texas -- 49.1 million out of its total 420 million hectares.

Some scientists, including Nobre, estimate that ecosystems in eastern, southern and central Amazonia are approaching a tipping point of 20 to 25 percent loss of native vegetation, beyond which the forest would no longer be able to survive in its current state (archived here and here).

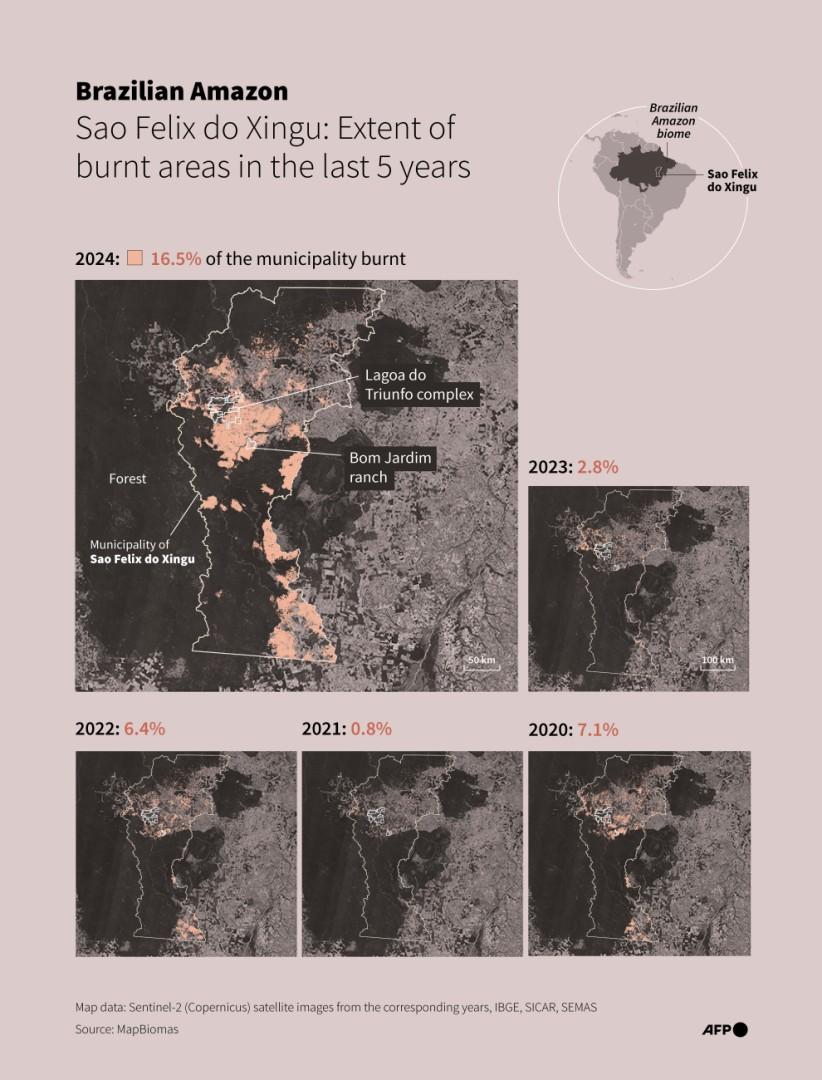

Brazil and Amazonian countries -- including Bolivia, Venezuela, Colombia, Peru, Ecuador and Guyana -- experienced a huge surge in fires in 2024.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), a consortium of independent scientists who release reports on climate for the United Nations, has documented such effects (archived here).

The increasing wildfire activity and high levels of deforestation have already turned parts of the Amazon into net-carbon sources, meaning certain areas emit more than they absorb (archived here).

Rates of deforestation remain stubbornly high despite a commitment by more than 140 leaders at the UN COP summit in 2021 to stamp it out.

COP30 aims to put forest preservation back on the global agenda.

Host city Belém is a symbolic yet fraught setting and a personal choice of Brazil's President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, who wants to spotlight the rainforest's role in absorbing carbon dioxide.

Pressure is mounting on the event -- dubbed by some as the "forest COP" -- to provide more than just a scenic backdrop as the world approaches the warming target agreed under the Paris climate accord in 2015 (archived here).

AFP has previously debunked climate contrarians' misrepresentations of other studies.

Copyright © AFP 2017-2026. Any commercial use of this content requires a subscription. Click here to find out more.

Is there content that you would like AFP to fact-check? Get in touch.

Contact us