No, Canada did not ban Christianity from the classroom

- This article is more than seven years old.

- Published on August 9, 2018 at 22:05

- Updated on August 10, 2018 at 15:40

- 3 min read

- By Louis BAUDOIN-LAARMAN

A widely-shared article claims that Canada has “banned Christian schools and colleges from teaching Biblical values.” While the Supreme Court of Canada upheld a decision by provincial law societies not to accredit a Christian university’s law school, this does not broadly affect religious education in Canada.

An article, shared over 14,000 times on social media, trumpeted an imaginary ban on Christianity in Canada’s classrooms, because “the Bible does not support the Trudeau government’s vision of ‘diversity’ and is therefore ‘harmful’ to LGBT and Muslim students.”

Your News Wire was alluding to a recent legal battle between the British Columbia-based Trinity Western University (TWU), an Evangelical Christian institution, and several provincial law societies over the university’s proposed law school.

In a judgement rendered on June 15, 2018, the Supreme Court of Canada sided 7-2 with the Law Society of Upper Canada and the Law Society of British Columbia in their decision not to grant an accreditation to TWU’s proposed law school.

The law societies argued that TWU should not be accredited because of a clause in the mandatory community covenant that its students must abide by. In signing, students agree to abstain from “sexual intimacy that violates the sacredness of marriage between a man and a woman.”

This clause was deemed discriminatory by the law societies as it implied that any sexually active LGBTQ student -- married or not -- would be in breach of the covenant and potentially exposed to expulsion.

Trinity Western appealed the decision on the grounds that preventing the school from promoting its values infringed on its religious rights. It argued TWU is a private institution whose students choose to sign the covenant based on Biblical values. However, the Supreme Court of Canada decided it was “proportionate and reasonable” to limit religious rights to guarantee equal access to LGBTQ students.

Beyond questions of religious freedom and access to services, Canada did not ban Christianity from its classrooms. Whether at the primary, secondary or postsecondary level, private Christian schools are legal, and sometimes even funded by the state.

At the primary and secondary level, over 50 Christian school boards in Canada have a separate status and are publicly funded, in addition to Christian private schools. At the postsecondary level, Christian Higher Education Canada (CHEC), an association of Christian higher learning institutions, counts 34 private institutions.

The claim that the Supreme Court’s decision stemmed from the fact that “the Bible does not support the Trudeau government’s vision of ‘diversity’ and is therefore ‘harmful’ to LGBT and Muslim students” is equally erroneous.

“The Supreme Court of Canada is an independent judicial body that is above government interference in its decision-making.” Cheryl Mines, director of the David Asper Centre for Constitutional Rights at the University of Toronto, told AFP.

The Canadian prime minister does appoint members of the nine judge court, but only after an independent committee reviews candidates and makes recommendations. Since Justin Trudeau came into office in 2015, he has appointed two Supreme Court justices, which would not have been enough to tip the 7-2 verdict had another prime minister appointed different judges.

Additionally, the two court documents do not mention Muslims.

The Your News Wire article foretells that “Christian colleges and universities will be stripped of their accreditation if they continue to promote Biblical standards and values.”

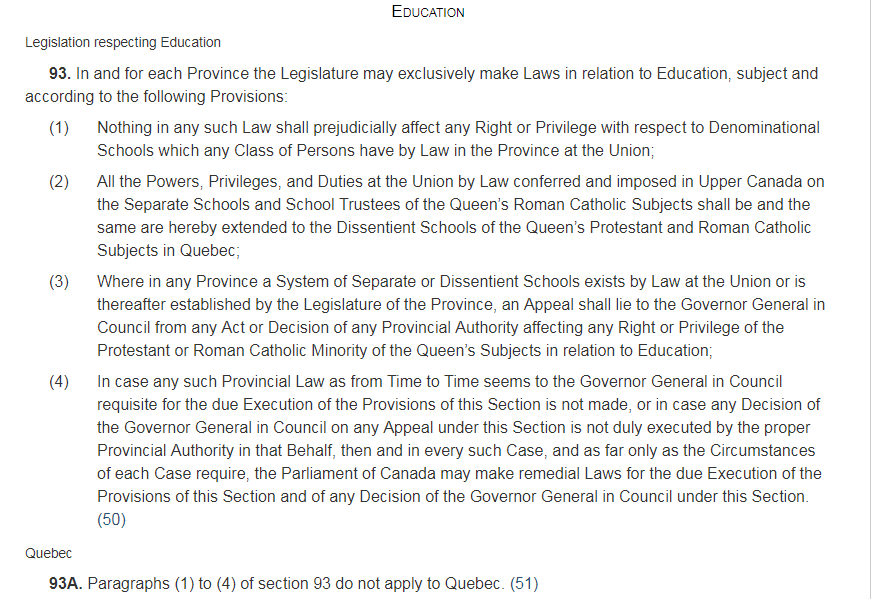

No authority in Canada can decree a country-wide rule on education. The Constitution Act of 1867 made education a provincial matter. Furthermore, the Supreme Court’s ruling in June 2018 only concerned TWU.

This ruling did not ease the concerns of Michael Pawelke, vice-chair of CHEC. He told AFP, “I do think there’s a concern in Christian higher education circles, and in institutions of Christian higher learning that there may be other sectors of accreditation or certification that may be challenged.”

The Asper Center’s Mines told AFP that challenges to already existing schools are “not likely because the decision to accredit them has already been made,” but added that professional bodies may look at the TWU decision for guidance.

The TWU law school was originally due to host its first 60-student cohort in 2015, and would have been the first private law school in Canada.

When contacted by AFP, Earl Phillips, lawyer and would-be executive director of the TWU law school, did not rule out the possibility that the law school would open in the future.

Phillips declined to comment on the Your News Wire interpretation of the Supreme Court ruling.

Copyright © AFP 2017-2026. Any commercial use of this content requires a subscription. Click here to find out more.

Is there content that you would like AFP to fact-check? Get in touch.

Contact us