These statues were not intended as a tribute to drowned slaves — but the artist is glad they are ‘stimulating debate’

- This article is more than six years old.

- Published on December 19, 2019 at 10:47

- Updated on January 8, 2020 at 09:01

- 3 min read

- By AFP Ethiopia, Amanuel NEGUEDE

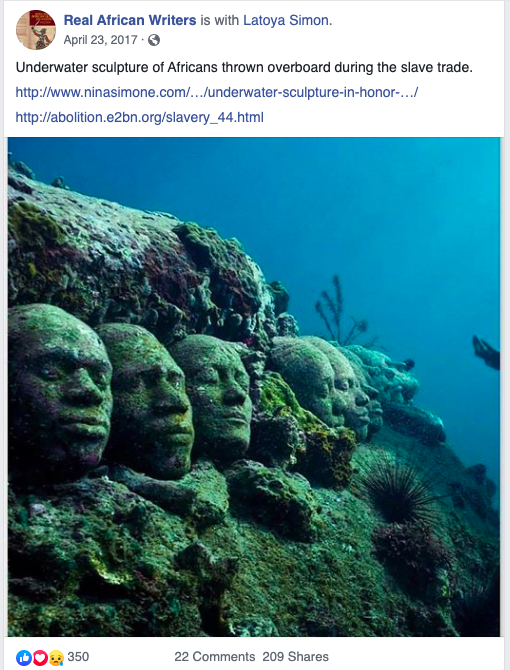

The claim has been shared on Facebook, including here and here, as well as on blogs here and here.

Chakabars, an Instagram star with more than 700,000 followers, also shared the claim in a post that was liked more than 14,000 times.

A reverse image search using Yandex revealed that these pictures were in fact taken at the Molinere Underwater Sculpture Park, a snorkelling site off the coast of Grenada. As reported in various posts, the statues are indeed located in the Caribbean Sea.

The link to the slave trade has evidently become widespread since the sculpture park was built in 2006, because the artist who created them, the British sculptor, photographer and environmentalist Jason deCaires Taylor, clarified in 2012 that they had not been intended as such a tribute.

“It was never my intention to have any connection to the Middle Passage,” he told the website The:nublk, referring to the part of the slave trade when Africans were forced onto ships and transported, in terrible conditions, across the Atlantic to the West Indies.

“Although it was not my intention from the outset I am very encouraged how it has resonated differently within various communities and feel it is working as an art piece by questioning our identity, history and stimulating debate,” the artist added.

If you look closely at the figures in “Vicissitudes”, one of the statues frequently linked to the slave trade claim, you’ll see that some of the figures are wearing jeans -- clothing that would not have been worn during the most of the period covered by the slave trade. In the United States, president Abraham Lincoln declared the emancipation of slaves from 1863, although the trade continued in Cuba and Brazil until the 1880s.

The garment we would recognise today as a pair of denim jeans was first patented by Jacob Davis and Levi Strauss in 1873.

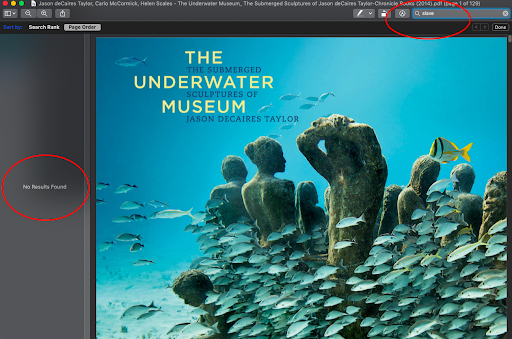

Additionally, AFP ran a search through the e-book version of “The Underwater Museum”, a book on deCaires Taylor’s work which includes essays by art critic Carlo McCormick and marine biologist Helen Scales. The word “slave” does not appear in the book’s 129 pages.

Jason deCaires Taylor confirmed in an email to AFP that his works are not related to the slave trade.

According to his website, deCaires Taylor’s underwater statues are built using pH-neutral materials “to instigate natural growth and the subsequent changes intended to explore the aesthetics of decay, rebirth and metamorphosis”.

Records documenting the slave trade are far from complete, and estimates for the number of Africans who were transported across the Atlantic vary widely. According to Martin Lynn, the late professor of African History at Queens University, Belfast, estimates have ranged from 20 million to 40 million, while around one in six are commonly believed to have died on the journey.

The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, a project run by researchers at several US universities, has gathered together maps and estimates from surviving documents -- you can check out the project here.

Copyright © AFP 2017-2026. Any commercial use of this content requires a subscription. Click here to find out more.

Is there content that you would like AFP to fact-check? Get in touch.

Contact us