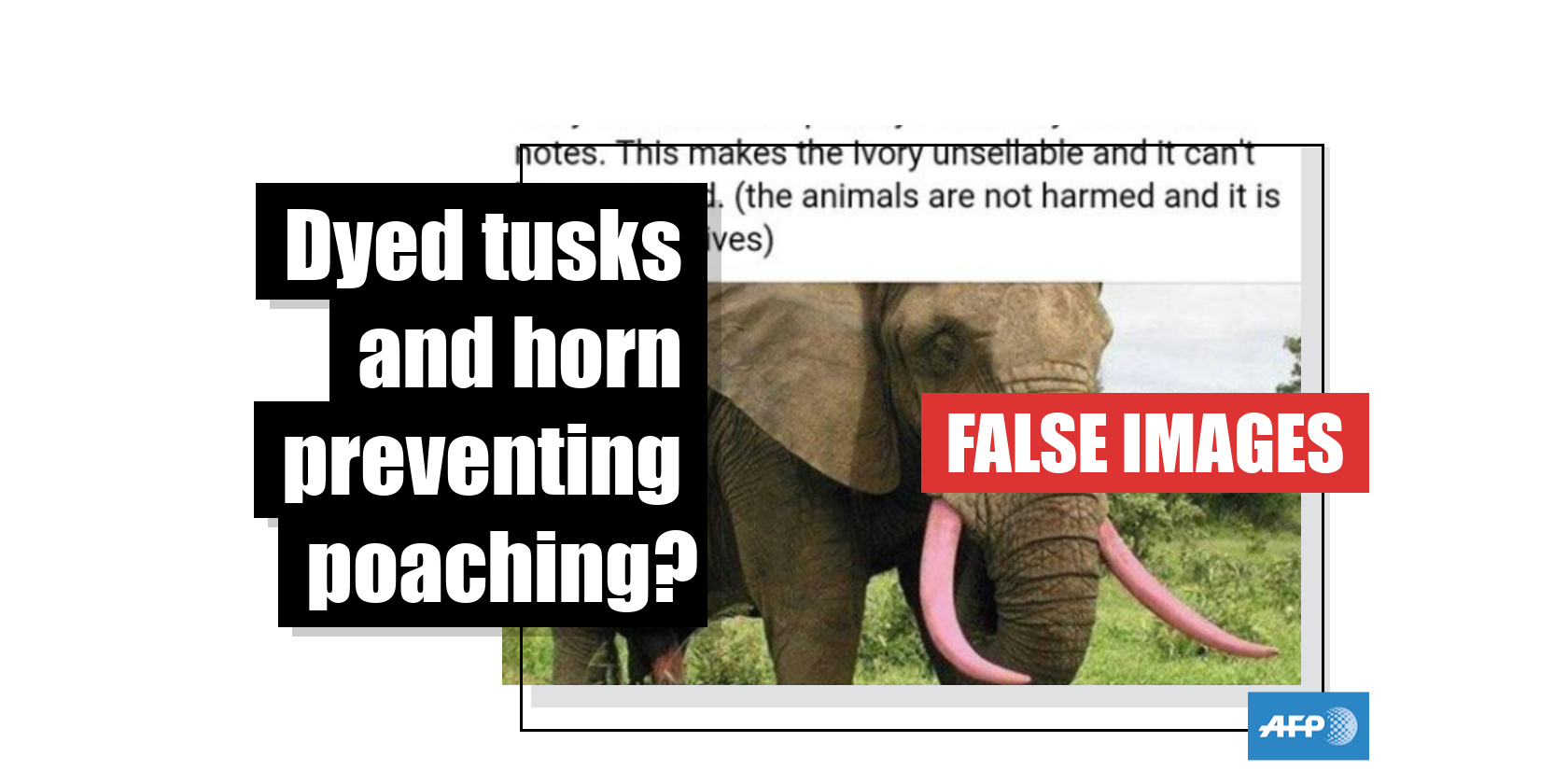

No, these tusks and horns were not dyed to make them worthless

- This article is more than six years old.

- Published on August 14, 2019 at 23:58

- 3 min read

- By Jean-Gabriel FERNANDEZ

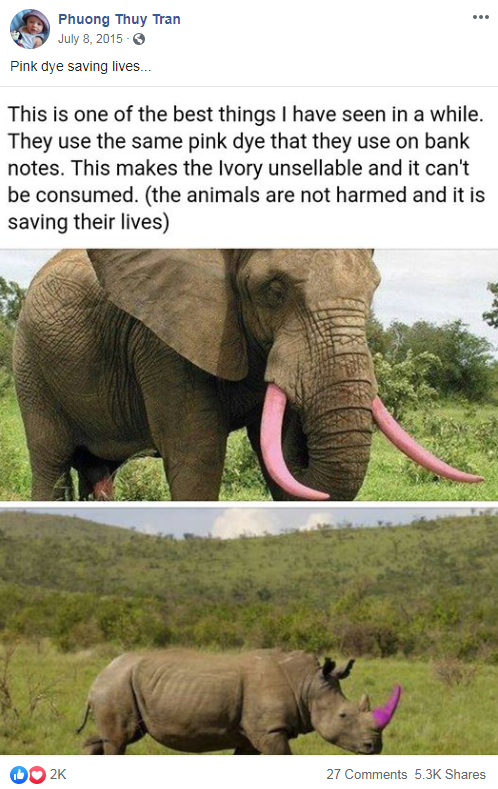

Dying elephants and rhinos’ tusks and horns pink does not prevent poaching. The idea that it does is very popular on the internet, as several petitions and social media publications in multiple languages show. This Facebook post alone has more than 5,300 shares and explains that pink dye “makes the Ivory unsellable and it can’t be consumed. (the animals are not harmed and it is saving their lives)”

This theory has been called the “pink tusk theory” in the United States. Unfortunately it is only a theory and does not work in practice.

Not enforceable

Several elements makes the dying of tusks and horns an unrealistic solution. This article on the website of the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) explains the logistical difficulties of attempting to dye the tusks of a population of 400,000 elephants.

In addition to requiring monumental financial resources, it would require the capture and sedation of the animals, which could put their health at risk.

“The perturbations and stress could cause harm on individuals as well as families, the number of animals that could succumb to the procedure has a good chance to be high” wrote Rikkert Reijnen, director of the program against wildlife crime at IFAW.

Moreover tusks grow constantly, which would require a regular repetition of the operation. “Even if it was doable, nothing guaranties that the pink ivory would not become the next trendy product” adds Rikkert Reijnen.

Stéphane Ringuet, in charge of the fight against trade of endangered species at the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), agrees. “It seems illusory to me to imagine that dying elephants’ tusks could have an impact on the behavior of poachers. Personally I don’t believe it for a second” he explained to AFP. He confirmed all the elements brought up by IFAW and added that “pink is very easily seen in nature, which would attract the attention of anyone, poachers included”.

For Ringuet, “This should not distract us from other actions that are more important in the fight against poaching, illegal trade or reducing the demand (for ivory).”

To fight against poaching, the WWF focuses primarily on education in order to reduce the demand for these products.

Making ivory toxic for humans

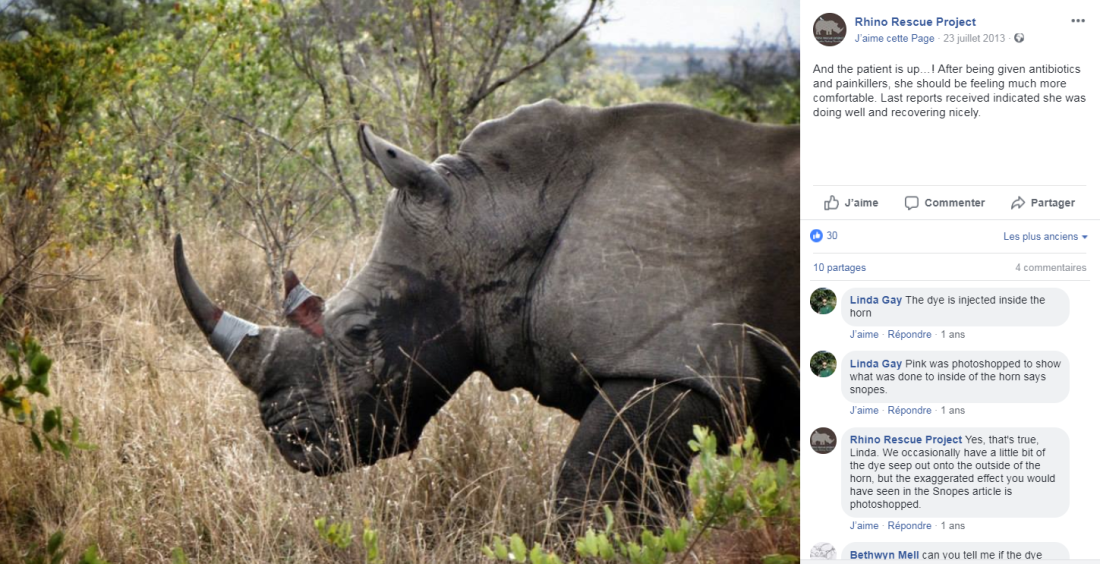

The inspiration for the pink dye story is an initiative by the Rhino Rescue Project, an animal protection association that developed a substance which made rhinos’ horns toxic for human consumption. It was created in the hope of dissuading poachers.

Tested in a South African protected park, a side effect of this substance gave horns a neon pink tint when they passed through airport X-ray machines, as shown in this AFP video.

However this pink shade could be seen by the naked eye, as this photo of a rhino after treatment from the Rhino Rescue Project shows.

This was all that was needed for the rumor to spread. Although elephants were never part of the initiative, Earth’s largest land mammal became part of the story.

The WWF estimates that at least 20,000 elephants are killed each year for their ivory.

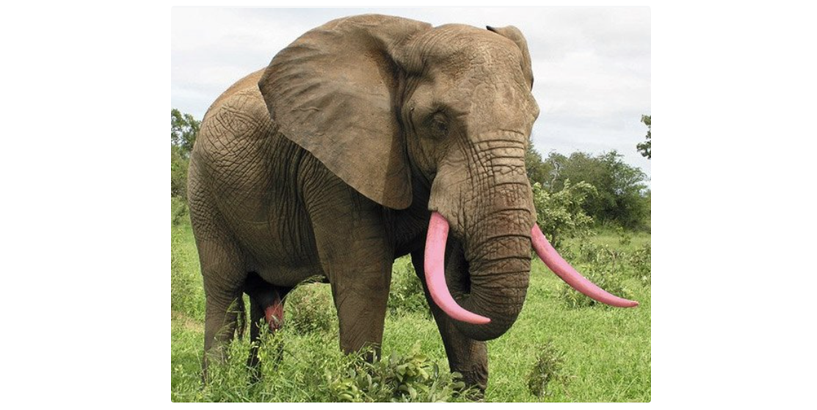

Doctored images

In the original picture, the elephant’s tusks are not pink, as can be seen in this video from 2011 :

Similarly, the rhino’s photo has been digitally altered. The original photo is available in various online image banks. It was taken by photographer Heinrich Van Den Berg.

Copyright © AFP 2017-2026. Any commercial use of this content requires a subscription. Click here to find out more.

Is there content that you would like AFP to fact-check? Get in touch.

Contact us