Hard drug sales remain illegal in British Columbia despite decriminalization

- This article is more than two years old.

- Published on February 23, 2024 at 21:34

- 4 min read

- By Gwen Roley, AFP Canada

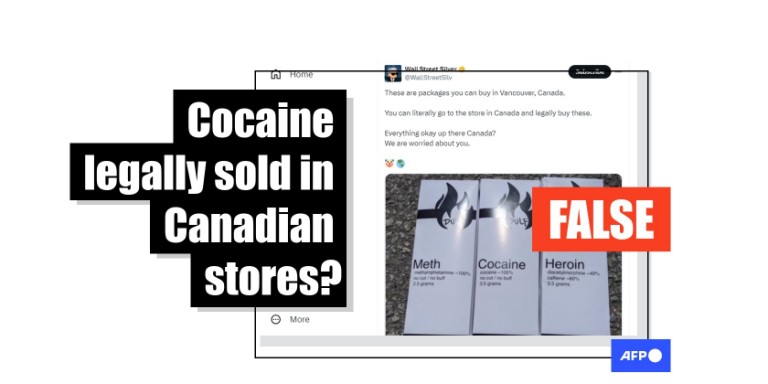

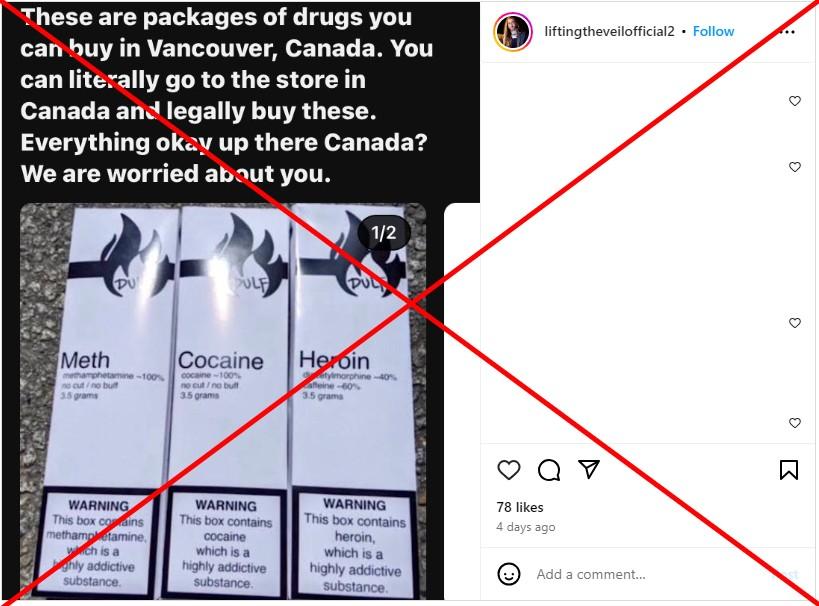

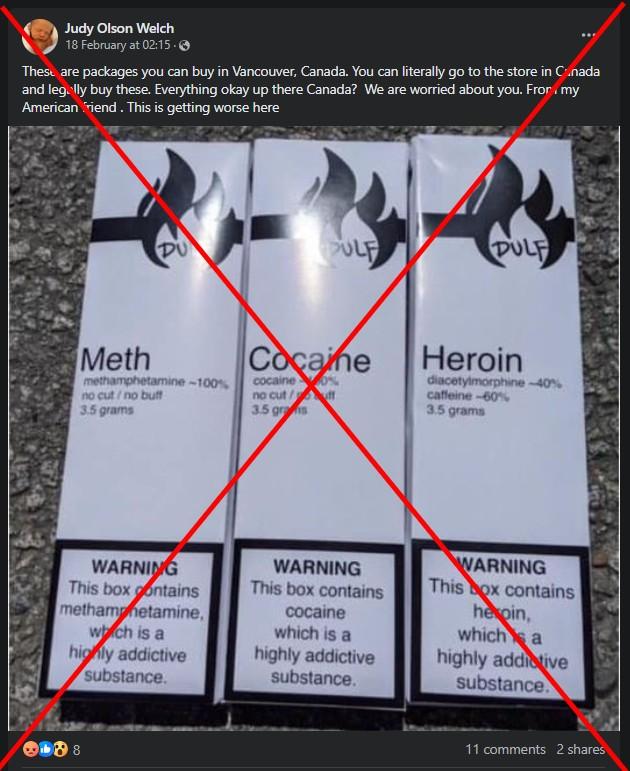

"You can literally go to the store in Canada and legally buy these," claims a February 17, 2024 post on X, formerly Twitter, by Wall Street Silver -- an account AFP has previously fact-checked for misinformation -- sharing a photo of three white boxes neatly labeled as meth, cocaine and heroin.

Other posts on Facebook, Instagram and X -- some in Spanish, Turkish and Slovenian -- spread with the same image and the claim that the drugs were legally sold in Vancouver and could be bought in Canadian stores.

False claims have spread in the past that British Columbia had legalized some drugs, but the province's Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions (MMHA) confirmed to AFP in a February 21 email that this is still not the case.

In January 2023, the province received an exemption from the federal government to launch a three-year pilot program of decriminalization which allows the possession of 2.5 grams or less of illegal opioids, cocaine, meth and MDMA without criminal penalties (archived here).

"But decriminalization is not legalization. Trafficking of illegal substances remains illegal under the federal Controlled Drugs and Substances Act," the MMHA said in its email (archived here).

Possession of quantities over the 2.5 gram limit is illegal and cannabis remains the only previously controlled substance now legally sold to the public (archived here).

While there have been reports of a store opening to sell drugs, this was deemed illegal. Companies granted federal licenses to sell cocaine may provide it only for research and narrowly prescribed medical uses and are not permitted to commercialize it on the open market.

Origin of the photo

Reverse image searches indicate the photo appeared online as early as July 2021 in posts discussing the Drug User Liberation Front (DULF), a nonprofit advocacy group seeking to reduce overdoses (archived here) by distributing drugs tested for purity.

The initials DULF match the logo seen on the boxes in the photo and pictures on the organization's website.

The MMHA said that DULF had a funding agreement with the Vancouver Coastal Health Authority (archived here) to check drugs and provide harm reduction services, but this contract was terminated when the organization was accused of engaging in illegal activity.

AFP reached out to DULF which declined to comment. But documents on its website describe how the organization's "compassion club" would distribute tested street drugs to a small group of people (archived here).

Another publication shared by members of the group described the project as "unsanctioned" (archived here).

According to reports, DULF's offices were raided and its co-founders were arrested in 2023, but they have not been charged as of February 23, 2024.

Thomas Kerr, the head of the Division of Social Medicine at the University of British Columbia, said that the provisions of a "safer supply," combined with decriminalization in the province still did not mean the sale of drugs is permitted.

"You can't go into a store and buy drugs in British Columbia, that's just ridiculous," he said.

Opioid crisis mitigation attempts

Overdose levels in Canada have been called a "crisis," with 19.3 out of 100,000 deaths in the country attributed to apparent opioid toxicity in 2022, according to Statistics Canada (archived here). In that year, rates of mortality from apparent opioid toxicity were highest in British Columbia, where it accounted for 45.2 deaths per 100,000 (archived here).

Both the MMHA and Kerr said the purpose of the drug decriminalization program in the province was to reduce stigma around drug use by recognizing addiction as a health issue and not a criminal one.

"It's to try and avoid arresting and incarcerating people who are really struggling with addiction and keeping them out of the criminal justice system," Kerr said.

Critics of the policy have said that allowing easier access to drugs has not reduced deaths from overdoses and has increased the level of public drug use.

"There's a lot of questions about this policy -- I think people just assume it's going to be beneficial," Kerr said. "But I think a lot of experts in the field are questioning that and are eagerly watching to see what happens."

Separately from decriminalization, Kerr said the provincial health system is also moving forward with medical-grade opioid prescriptions for users to reduce the level of risk associated with acquiring and taking the drugs (archived here and here).

Read more of AFP's reporting on misinformation in Canada here.

Copyright © AFP 2017-2026. Any commercial use of this content requires a subscription. Click here to find out more.

Is there content that you would like AFP to fact-check? Get in touch.

Contact us