Canadian province temporarily decriminalized, not legalized, some drugs

- This article is more than three years old.

- Published on June 9, 2022 at 20:10

- 3 min read

- By AFP Canada

"Starting next year, #Canada will legalize heroin, cocaine, and meth," claims a June 1, 2022 tweet shared and liked hundreds of times.

Similar claims also circulated on Facebook.

In early June, the Canadian government granted British Columbia a three-year exemption under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act to decriminalize possession of small amounts of some illicit drugs including opioids, cocaine, crystal meth, crack cocaine and MDMA for personal use.

A statement from Health Canada says: "This exemption is not legalization. These substances remain illegal, but adults who have 2.5 grams or less of the certain illicit substances for personal use will no longer be arrested, charged or have their drugs seized. Instead, police will offer information on available health and social supports and will help with referrals when requested."

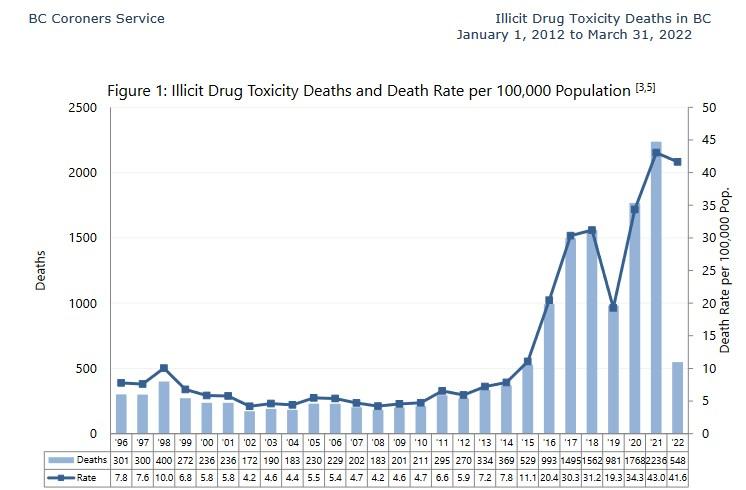

For years, Canada's westernmost province has been battling a "public health emergency" that has claimed thousands of lives to overdoses. The country's street drugs have become tainted with powerful opioids, such as fentanyl.

The province has been working to secure the exemption since April 2021, saying it wanted to "remove the shame that often prevents people from reaching out for life-saving help."

The approved pilot program is temporary and it does not mean that all drugs will be legally available to the public, according to independent experts.

Benjamin Perrin, law professor at the University of British Columbia, who published a book about Canada's opioid crisis, told AFP in an email: "Decriminalization is not legalization."

He explained that British Columbia will "no longer criminalize people for possessing small amounts of illicit drugs below a certain threshold -- that's decriminalization. Drugs are not being legalized, which would mean they could be purchased like cigarettes or alcohol."

He also said that while initiatives exist to help people with substance abuse disorders get access to drugs that have been checked for their contents, "these aren't freely available to the general public."

With the three-year partial decriminalization pilot, Perrin said the province is moving toward treating substance abuse as a health issue, not a criminal justice issue.

"Criminalizing people who use drugs isn't working. In fact, research shows it's making it worse," he said. "Criminalization contributes to stigma, people using alone, and using drugs faster to avoid detection -- all of which increases risk of overdose death."

Mark Haden, adjunct professor at the University of British Columbia's School of Population and Public Health, agreed.

He said in a phone interview that this pilot project marks a departure from the traditional criminal justice approach to drug policy.

"The first drug law in Canada was 1908 so we've had over a century to reflect on the evidence that a prohibition approach does not work and a health approach to drugs does work," he said.

He explained that people end up in the criminal justice system over very small drug possession charges and that by decriminalizing possession it will potentially reduce "people's involvement in the criminal justice system, which is healthier for all of us."

He also said the project would hopefully increase health service spending. "If we're reducing our expenses in the criminal justice system, hopefully we will increase our expenses in the process that actually works," he said.

Thomas Kerr, professor at the University of British Columbia and director of research at the BC Centre on Substance Use, said the policy is a "step in the right direction," but pointed out several shortcomings, including the fact that the program does not address the contamination of the drug supply or the possibility that the potency of drugs will change in response to the policy.

"There are also some concerns that this policy could actually serve to increase risk if people make more frequent purchases of smaller amounts of drugs in order to avoid purchasing more than 2.5 grams and hence arrest," he said.

The provincial and federal governments have pledged to monitor and evaluate the program and address any unintended consequences.

In 2018, Canada became the first G7 country to legalize recreational use of cannabis.

Copyright © AFP 2017-2026. Any commercial use of this content requires a subscription. Click here to find out more.

Is there content that you would like AFP to fact-check? Get in touch.

Contact us