More false claims about ‘Irish slaves’ spread on social media

- This article is more than five years old.

- Published on July 7, 2020 at 20:14

- Updated on September 16, 2020 at 16:08

- 6 min read

- By Alex CADIER, AFP Canada

The claims were shared more than 10,000 times in the US and Canada over a 10-day period to June 30, 2020, across multiple posts (here, here, here).

Screenshot of a Facebook post taken on July 7, 2020

Similar claims have been made across several posts spreading misinformation about slavery and Irish indentured servants, as fact-checked by AFP.

The “Irish Slaves Myth” seems to regularly gain traction in response to the surges in anti-racism protests and calls for reparations for African slavery, as explained here by Liam Hogan, an Irish librarian and historian.

Conflating slavery with indentured servitude

The core claim that Irish workers in the colonies were slaves is false. The term “indentured servants,” is more accurate.

There is ample evidence that “English, Welsh, Scottish, and Irish nationals desiring immigration to the island, but lacking the means to pay their passage and sustenance, voluntarily indentured themselves,” according to Jerome Handler, senior scholar at Virginia Humanities and Matthew C. Reilly, assistant professor of anthropology at the City University of New York.

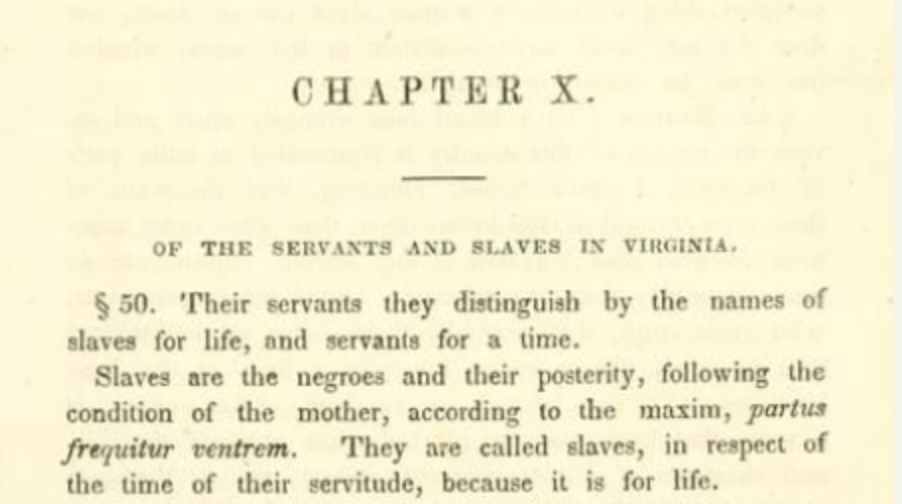

A distinction between indentured servants and slaves was cited as early as 1722 in the History of Virginia by Robert Beverley Jr.

“Slaves are the negroes [sic] and their posterity, following the condition of the mother, according to the maxim, partus frequitur ventrem. They are called slaves, in respect of the time of their servitude, because it is for life. Servants, are those which serve only for a few years, according to the time of their indenture, or the custom of the country,” he wrote.

Screenshot, taken on June 18 of an excerpt of Robert Beverley Jr’s History of Virginia (1722)

This is confirmed by Brendan Wolfe, editor of Encyclopedia Virginia: “Indentured servants were men and women who signed a contract (also known as an indenture or a covenant) by which they agreed to work for a certain number of years in exchange for transportation to Virginia and, once they arrived, food, clothing, and shelter.”

Unrelated photograph

The photograph used alongside the post, and described as a “representation,” does not depict Irish indentured servants, nor was it taken in North America, nor in the same century as claimed.

A reverse image search revealed versions of this photograph which can be found in historical blogs, on Pinterest and Reddit, claiming that it is of Italian miners in Belgium around 1900.

“This photo was taken around the end of the 19th beginning of the 20th century” Colette Ista, Assistant Director of the UNESCO World Heritage listed Bois Du Cazier mine museum in Belgium, told AFP via email.

“It shows a cage [elevator] in a Mariemont-Bascoup operated mine in central Belgium, located near the town of La Louvière.” added Ista, confirming that this photograph has no link to Ireland or the North American colonies.

The King James I 1625 proclamation

This list of Stuart royal proclamations, compiled by James Larkin and Paul Hughes and published by the University of Oxford, shows that King James I issued six royal proclamations in 1625, the year of his death. Contrary to claims in the post, none of them related to the treatment of the Irish.

However, an earlier proclamation issued by James I in 1603 “criminalized repeated vagabondage and idleness”, according to Hogan.

The punishment for this would be banishment to “New-found Land, the East and West Indies, France, Germanie, and the Low-Countries, or any of them,” it said.

“These ideological attempts to ‘correct’ poverty (through subjugation and forced labour) partly explain the disproportionately high level of forced transportations from Ireland to the American colonies,” Hogan said.

70 percent of Montserrat’s population were Irish slaves

It is true that the majority of the 1,000 families living on the Caribbean island of Montserrat in the mid 17th century were Irish, as written by Kevin Kenny in Ireland and the British Empire.

By the end of the 17th century, “nearly 70 percent of Montserrat’s white population was Irish” Kenny said, however, this number does not include the island’s native population.

As the island’s population was not exclusively white, the claim that 70 percent of Montserrat’s entire population was specifically Irish is false.

“These Irish settlers not only prospered but ‘became more economically powerful’ than their Scottish and English counterparts, largely because ‘they knew how to be hard and efficient slave masters,’” added Kenny, showing that the claim that the Irish in Montserrat were slaves, is also false.

300,000 Irish slaves sold into slavery

This claim is false.

“To put this into context, the total migration from Ireland to the West Indies for the entire 17th Century is estimated to have been around 50,000 people and the total migration from Ireland to British North America and the West Indies is estimated to have been circa 165,000 between 1630 and 1775,” Hogan wrote in this blog post.

It is accurate to say, as the post claims, that 500,000 people died in Ireland between 1641 and 1652, although this was due to the Eleven Years War: “The war had been extremely costly with a death toll of somewhere between 200,000 an 600,000,” Irish Historian John Dorney wrote.

“Despite losing some 20-40 percent of its population due to war and famine from 1641-53, Ireland’s population still doubled over the course of the 17th century from around one million to two million inhabitants,” Padraig Lenihan, a historian at the National University of Ireland, Galway told the Irish History Show.

More than 100,000 Irish children sold as slaves in the 1650s

Hogan wrote that this was another “massively exaggerated claim which does harm to the historical record of the officially sanctioned transportations and illicit kidnapping that did occur.”

“The most infamous case involved David Selleck, a prominent tobacco merchant from Boston, New England. On the 6 September 1653 a warrant was awarded to Selleck (after he had petitioned for it) to transport 400 Irish children into New England and Virginia.”

Hogan added that “despite the initial warrant to transport children they instead sought out adolescents and adults” who were “subsequently sold against their will as indentured servants” from one ship off Rappahannock, Virginia and another off New England.

Although conditions were very poor, and many were taken against their will, it is false to describe them as slaves, as they had terms of servitude and would be free once it had ended, unlike African slaves of the time who would remain enslaved for life, as described by historians Handler and Reilly, and in Beverley’s 1722 “History of Virginia”.

52,000 mostly women and children, sold to slavery in the 1650s

This claim is false, and brings into question how this could relate to the other claims about 300,000 Irish slaves or 100,000 Irish children, if such claims were true.

“This exaggerated figure of around 52,000 has lineage. It can be traced back to Sean O’Callaghan’s To Hell or Barbados. O’Callaghan incorrectly attributes this number to Aubrey Gwynn. But he either misread Gwynn or has deliberately misled the reader because Gwynn took a guess at 16,000 sent to the West Indies and his total estimate of 50,000 includes the 34,000 that left Ireland for the continent” Hogan wrote.

African slaves more expensive than Irish

There is no evidence to support this claim. In fact, it appears that African slaves were more economical than white indentured servants of the time.

“Planters eventually turned to black slaves as their principal source of bound labor,” wrote economist David Galenson. “The transition from servants to slaves, which occurred at different times in these regions, and at different rates, appears explicable in terms of the changing relative costs of the two types of labor faced by colonial planters.”

Forced breeding between Irish women and African slaves

“There is no evidence for any of these claims in the British West Indies and the British North American colonies. These ahistorical claims are part racialised sadomasochistic fantasy and part old white supremacist myth á la ‘The Birth of a Nation’ that heighten racist sentiment in the ‘Irish slaves’ meme,” wrote Hogan.

He points to this 1664 Act by British colonists which criminalized interracial marraige, stating that any white woman who married an African slave would have to serve as a life-long slave like her husband. Their children would too.

1,302 slaves dumped overboard by a British ship

This claim is similar to ones made in other social media posts, stating that 132 Irish slaves had been thrown overboard from an English ship. AFP did not find any historical evidence of 1,302 slaves being thrown off a British ship.

Many of the false claims in this post appear to come from a 2003 blog post by James F Cavanaugh, which cites little historical evidence. Although the website is now unavailable, an archived version can be found here.

According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, a non-profit organization that monitors hate groups throughout the US and exposes their activities to law enforcement agencies, posts like these have been “weaponized by racists and conspiracy theorists before the Web and now reaching vast new audiences online.”

Copyright © AFP 2017-2026. Any commercial use of this content requires a subscription. Click here to find out more.

Is there content that you would like AFP to fact-check? Get in touch.

Contact us