Trump, Republican lawmakers misrepresent jury instructions in hush money trial

- This article is more than one year old.

- Published on May 30, 2024 at 22:54

- 4 min read

- By Bill MCCARTHY, AFP USA

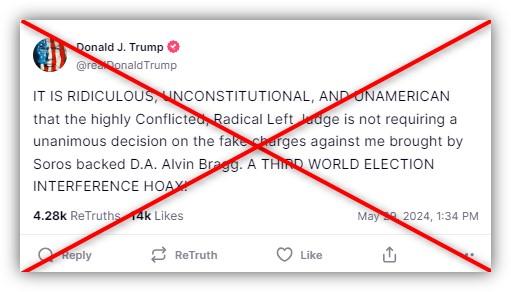

"IT IS RIDICULOUS, UNCONSTITUTIONAL, AND UNAMERICAN that the highly Conflicted, Radical Left Judge is not requiring a unanimous decision on the fake charges against me brought by Soros backed D.A. Alvin Bragg," Trump said in a May 29, 2024 post on Truth Social.

The businessman railed against what he called "A THIRD WORLD ELECTION INTERFERENCE HOAX" as deliberations began in the New York trial, where he faces 34 felony counts of falsifying business records related to a hush money payment to porn star Stormy Daniels ahead of the 2016 presidential election. The case is one of several facing Trump as he seeks a return to the White House in November's election.

Trump's claims echoed a widespread X post from Fox News co-anchor John Roberts, who said Merchan "just told the jury that they do not need unanimity to convict."

Soon, similar claims ricocheted across social media, amplified by many of Trump's supporters in Congress and the media.

"Judge in Trump case in NYC just told jury they don’t have to unanimously agree on which crime was committed as long as they all at least pick one," Republican Senator Marco Rubio said on X.

But legal experts say the claims misrepresent the instructions Merchan gave to the 12-member jury who will decide Trump's fate.

"It is wrong to say that the judge told the jury they don't need unanimity to convict," David Alan Sklansky, co-director of Stanford University's Criminal Justice Center, told AFP in a May 30 email (archived here).

In fact, a single holdout among the jurors would result in a hung jury and mistrial.

Trump's charges, Merchan's instructions

Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg charged Trump with falsifying business records in the first degree, accusing him of covering up reimbursement payments to then-lawyer Michael Cohen, who paid Daniels for her silence over a past sexual encounter that could have impacted Trump's 2016 presidential bid.

The charge is a felony under New York law -- a step up from the misdemeanor of falsifying business records in the second degree. They differ in that the felony requires not only an intent to defraud but also "an intent to commit another crime or to aid or conceal the commission thereof" (archived here and here).

The underlying crime prosecutors allege Trump intended to commit, aid or conceal is a violation of a state election law that prohibits conspiring "to promote or prevent the election of any person to a public office by unlawful means" (archived here).

When reading his instructions May 29, Merchan said the verdict on each of the 34 felony counts "must be unanimous" (archived here).

However, he noted that jurors do not need to reach a consensus on what "unlawful means" Trump may have taken to influence the election -- prompting the slew of false claims online about unanimity.

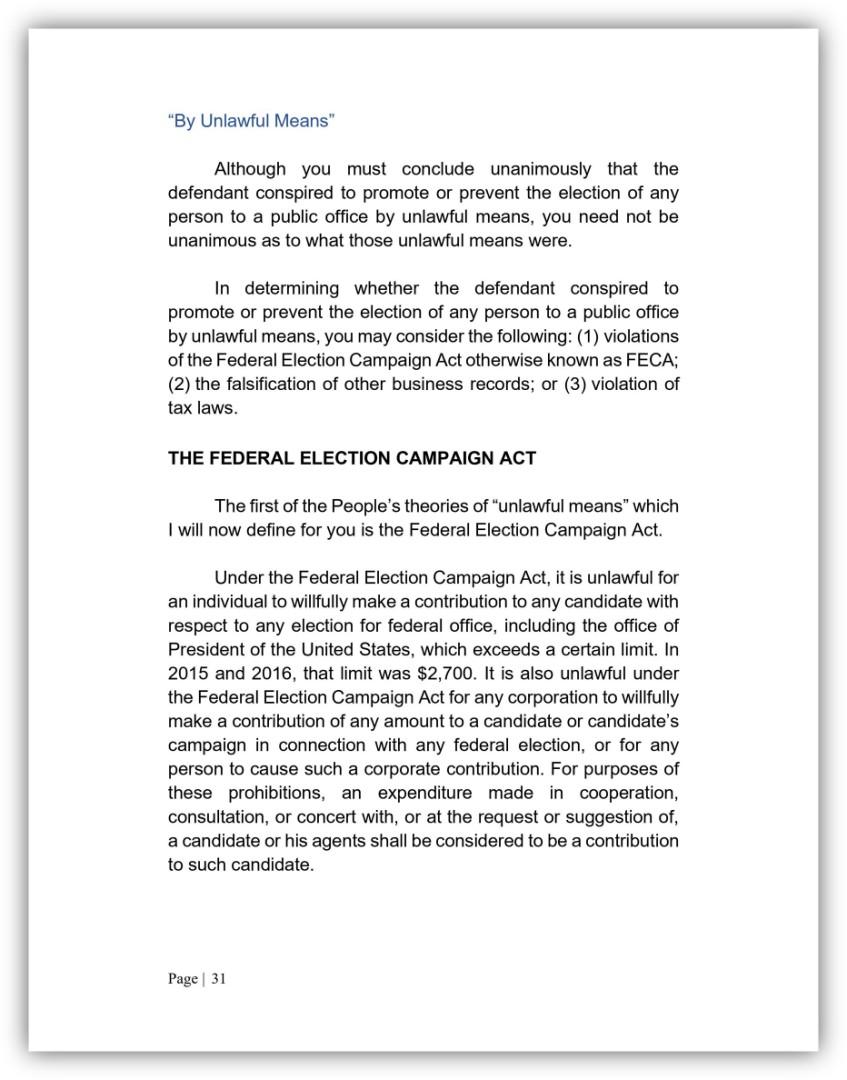

"Although you must conclude unanimously that the defendant conspired to promote or prevent the election of any person to a public office by unlawful means, you need not be unanimous as to what those unlawful means were," Merchan said.

He listed for the jury three of the prosecution's theories: federal election law violations, tax law violations or the falsification of other business records.

He also told jurors they "need not be unanimous on whether the defendant committed the crime personally, or by acting in concert with another, or both."

"The distinction is between an element of the offense and a means of committing it," Randall Eliason, a former US attorney who teaches law at The George Washington University, told AFP in a May 29 email (archived here).

"The element of the offense is that Trump falsified the documents in order to conceal another crime, in this case conspiring to interfere with an election by unlawful means. The jury must unanimously agree on that. But they don't have to be unanimous on what the particular unlawful means were, and the prosecution offered three different possibilities."

Roberts, the Fox News personality, clarified in follow-up posts that the jurors can diverge on how Trump may have carried out the alleged violation of state election law, but not on whether he is guilty of falsifying business records.

Standard in criminal cases

Sklansky of Stanford told AFP that Merchan's instructions are not a departure from the norm.

"It is common in criminal cases for juries to be told that they don't have to agree unanimously on the details of how a charged crime was committed," he said.

Ric Simmons, a professor of law at The Ohio State University who previously worked as a prosecutor in New York County, agreed (archived here).

"None of these rules were made up by the judge or the district attorney," Simmons told AFP in a May 29 email. "This is standard New York state law that was passed by the legislature and approved by appellate courts decades ago and which has been applied in exactly this way in tens of thousands of falsifying business records cases before Trump."

Simmons and Eliason likened the case to the way burglary is prosecuted.

Such convictions require proof that the defendant knowingly entered or remained unlawfully on a property with the intent to commit another crime, such as theft. A prosecutor does not have to specify what other crime the defendant planned to commit -- and jurors can disagree, so long as they all believe beyond a reasonable doubt that the person intended to commit a crime.

"Literally, hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers have been convicted of burglary under these rules," Simmons said.

Other experts have offered similar analogies on X.

AFP has debunked other misinformation about Trump's trial here, here and here.

Copyright © AFP 2017-2026. Any commercial use of this content requires a subscription. Click here to find out more.

Is there content that you would like AFP to fact-check? Get in touch.

Contact us