Experts refute comparisons of US cattle, bison climate impact

- This article is more than two years old.

- Published on December 18, 2023 at 22:38

- 3 min read

- By Manon JACOB, AFP USA

"1820: 30 million bison roam North America. Climate is normal," says a December 8, 2023 Facebook post from a page called "Climate Change is Crap."

"2020: 30 million cattle roam North America, DANGER, CLIMATE EMERGENCY! Go vegan!"

Similar claims have previously circulated on X, formerly known as Twitter. They resurfaced amid calls for reducing greenhouse gases such as methane at COP28 in Dubai.

But the population numbers shared online are inaccurate, according to animal science experts -- and the climate impact of wild bison and livestock differs due to their feeding habits.

"The comparison in the tweets is misguided at best," said Ermias Kebreab, director of the World Food Center at the University of California-Davis.

He said there is no good data on historical bison populations, but "most estimates put them around 60 million." In contrast, there are about 90 million heads of cattle in the United States, according to data from the Department of Agriculture (USDA) (archived here).

"So yes, there is more methane being emitted now compared to pre-industrial levels," Kebreab said in a December 13 email.

Methane's warming role

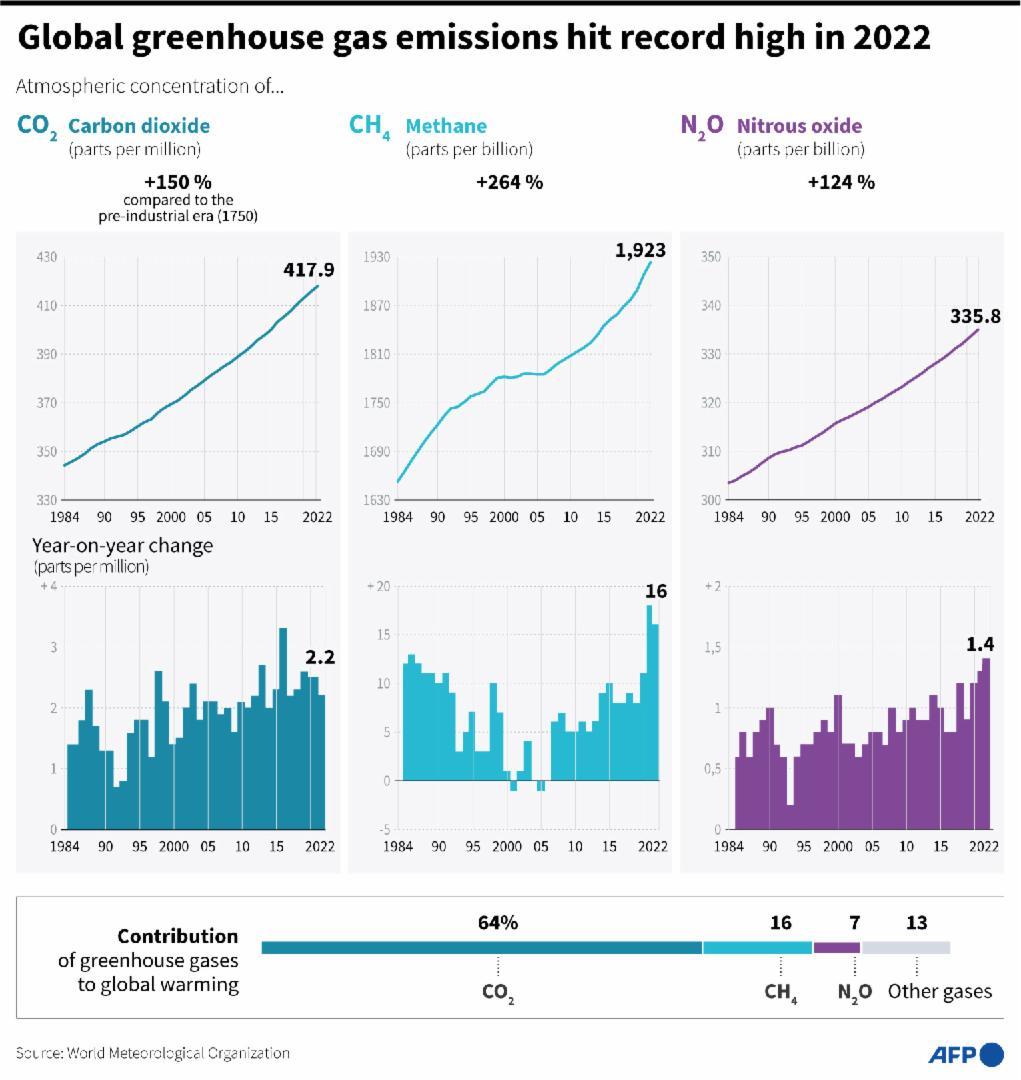

Methane is a primary component of natural gas and represents about a third of global warming, according to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (archived here). It is short-lived but one of the most powerful greenhouse gases -- 28 times as potent as carbon dioxide.

The EPA says methane concentrations in the atmosphere have more than doubled over the past two centuries, largely due to human activity.

In 2021, methane accounted for 12 percent of all human-caused greenhouse gas emissions in the United States, according to the EPA (archived here).

"Out of the observed increase of 1.1C in global temperatures since pre-industrial levels, about 0.5C can be attributed to methane emissions because of its potent ability to trap heat," Kebreab said.

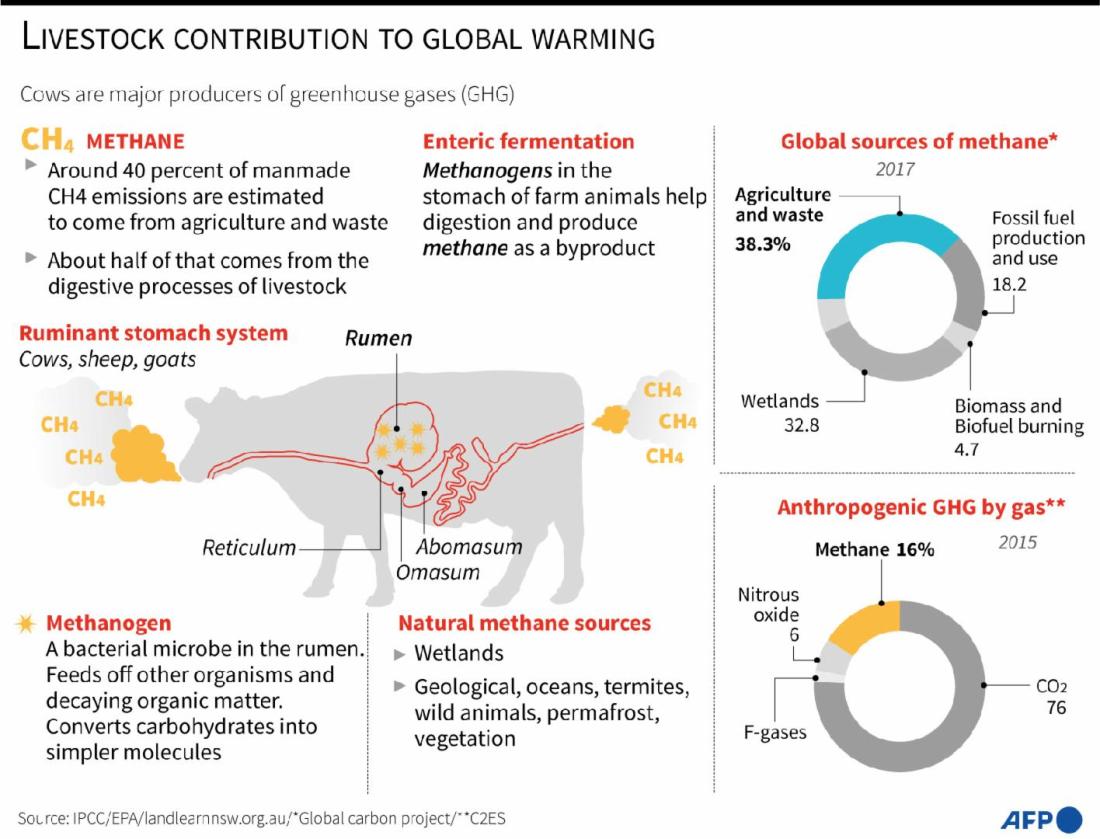

Cattle produce methane through their digestive process (archived here), making agriculture a top contributor of the greenhouse gas. The sector's emissions rose by about 15 percent between 1990 and 2021, according to EPA data (archived here).

Myles Allen, a professor of geosystem science at Oxford University, previously told AFP that "global livestock numbers and associated methane emissions are going up, causing lots of global warming."

Different feeding habits

Beyond their population size, part of the reason modern livestock are a significant source of methane has to do with how much they eat.

"When fed similar feed, bison and cattle appear to have similar methane fluxes," said Paul Stoy, an associate professor in the Department of Biological Systems Engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, in a December 15 email.

"We're not entirely sure if bisons had lower methane fluxes in the past as they were able to graze and eat more nutritious grasses and forbs that are easier for them to break down ... but a conservative estimate is that the fluxes are approximately the same on a per-animal basis."

However, modern cattle and bison differ in how much they consume.

Bison eat 1.6 percent of their body mass per day -- or about 24 pounds for a 1,500-pound bison, according to the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (archived here).

In comparison, some dairy cows eat as much as 100 pounds of food per day, according to the USDA (archived here).

"So total emissions per animal is more due to differences in intake," said Kebreab of UC-Davis.

Livestock farming has been expanding in the United States and worldwide to meet the growing demand for meat, underscoring concerns about emissions.

Since 1990, agricultural methane emissions have increased in the US largely driven by increased livestock production and the low-cost, emissions-intensive manure management techniques on large-scale dairy and swine operations, a 2022 report published by the University of Michigan states (archived here).

Scientists say cutting such emissions, as well as other greenhouse gases, is essential to limit the rise of average global temperatures to 1.5 degrees Celsius -- a threshold for avoiding the worst effects of climate change (archived here).

A new draft agreement at COP28 called for "accelerating and substantially reducing non-CO2 emissions, including, in particular, methane emissions globally by 2030."

AFP has debunked other false and misleading claims about climate change here.

Copyright © AFP 2017-2026. Any commercial use of this content requires a subscription. Click here to find out more.

Is there content that you would like AFP to fact-check? Get in touch.

Contact us